A Chilling Wake-up Call

by Chris Banks (mr.banks@temple.edu)

Published in the Philadelphia Daily News on July 11, 2007

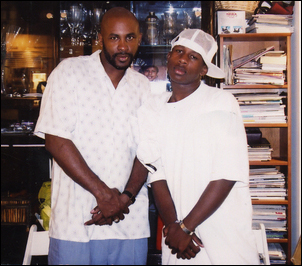

I'll always remember my dad giving me the finger when we made eye contact at my high school football games.

No, not that finger, but his index finger pointed at me, indicating, "Son, I'm here. I see you!"

I would smile under my helmet and finish the game. It was a personal thing that we did so that I could locate him in the crowd. I'm sure many people can recall a "personal thing" they remember about my dad. He was one of those guys who always left a lasting impression. When you really got to know him, you couldn't help but love him.

On Sunday, March 18, I was awakened at 8:30 a.m. by a homicide detective who said, "Chris, I need to see you for an important matter regarding your father."

He told me that my dad, Marlon Banks, 42, had been shot and killed on the streets of Philadelphia. He had been found dead early Sunday at Royal and Logan in Germantown, outside his black Mercedes, shot five times.

It was a message that I will forever regret having to hear.

My dad loved me and all my siblings. Despite us having different mothers, he always tried to keep us together as a close-knit family and show us what family was all about. Doing the little things that kept us together, like cooking when we were hungry (while knowing that he couldn't cook very well!) or taking us for a weekend visit to Dave & Buster's even if that was his last round of money until the next paycheck.

The tears, the love and the sacrifice are what separated him from most. He was an honest man who did what he had to do to fulfill his role as a provider.

There were 406 homicides in Philadelphia last year. We were ranked sixth in homicides in 2006 among big cities, and we have more than 200 murders in a little more than half of this year.

And still, we don't get it!

What will it take for us inner- city youths to realize that the streets are not the way? How close to home does it have to hit? A co-worker? A homie?

Girlfriend? Boyfriend? What about a best friend? And what if that best friend was your parent? Well, that's what it took for me.

I can still remember talking to him every day. Every conversation had its jewels of wisdom. They were mostly about comparing good and bad, school and streets, or the famous "thug or jock" lecture that I heard so often. All with deep detail, making the point that there is no long-term success in the evils of drug- dealing and killing.

And how you can't play on both sides of the field because the streets will always win in the long run. The best way, he always said, is to stay away.

The knowledge that he instilled I take with me every day to help myself and others.

It seems like too many young people glorify the street life for the short-term money, the "fame" and the temporary "respect." Maybe it's because they feel like they can't be caught or stopped, or that the life is just too good to let go.

Whatever the case may be, no one ever looks at the flip side of things. Because if they did, there's no way they would want this side for their family.

Every day, bad schools and poverty push young black men to become ignorant rappers instead of motivational speakers, drug dealers instead of successful salesmen, and street killers and gunslingers instead of police officers or soldiers.

But it's up to us to break the pattern. I put the burden on my peers (I'm a 19-year-old African- American) because it has to start somewhere, and we're the foundation of the crime demographic.

The streets don't come to you when you're 42, but earlier - in high school, middle school and even, sadly, elementary school.

On a sunny day like the day I'm writing this, I probably would call my dad at about 7:30 a.m. before I go to school, just to ask what's up. If I had time, I would go to ChopStick & Fork, our breakfast spot at 28th and Girard, to get turkey bacon, grits and pancakes with a medium cup of coffee (his daily ritual).

I'd go to school and then meet up with him afterward, somewhere in North Philly. We would hang out and talk for a while until one of us was tired.

"All right, Dad, I'm out," I would say.

"All right. What, you going to meet up with Saadiq? The twins?" he'd reply, referring to my brother and my best friends.

"All right. Just make sure you wake me up for work at 10. I'm going home."

And after every conversation, he would add - even on the night of his death, "Hey, dog! You know I love you, right?"

And because he said it so often, I would nonchalantly reply, "Yeah, yeah."

But I know he meant it.

And I really miss him.

* This essay was originally prepared for Professor Miller's J260 Journalism Research class during the spring 2007 semester.