Ball of Confusion

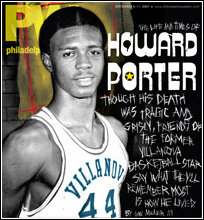

Though his death was tragic and grisly, friends of former Villanova superstar Howard Porter say what they'll remember most is how he lived.

From the September 5, 2007 Philadelphia Weekly

This is a story about heroes.

Of little boys listening to games on transistor radios and dreaming of hearing their names squawked over the airwaves.

Of neighborhood rivalries, city pride and lifelong relationships.

Of manhood, trials and tribulations, and redemption.

This is not a murder mystery.

It just starts with one.

***

The sun is slowly rising on this Saturday morning, casting a faint orange glow over this deceptively suburban-looking neighborhood of modest single-family homes built in the mid-20th century.

At 5:30 a.m. an older couple stroll out of their home, which faces a large, lush green park with baseball fields, trees and swing sets. They walk their two Chihuahuas up the road, down the alley that provides access to rear parking and back up the block.

They rise early, the safest time of day in this area that's among the most dangerous and drug-infested sections of Minneapolis. A few months back a man was shot twice while sitting in his car on the corner at 7:30 in the morning as children were walking to school.

Gunshots and shrieks arrive like rain or thunder here, only more predictably. People stay indoors when possible. "For sale" signs sprout from overgrown lots on every block.

As the couple make their way down a cracked concrete alley lined with trash cans and crumbling garages, they see a rolled-up rug lying in the middle of the narrow passage.

Getting closer, the man backs up and holds his arm out to stop his wife. "Oh my God," he says.

The rug is bloodstained. Legs are poking out from one end. One foot is missing a shoe.

The man in the carpet - beaten to near death - is taken to nearby North Memorial Medical Center. Lacking identification, he's admitted as John Doe.

***

A day after the bloodied man in the rolled-up carpet was discovered, a female hospital worker identified him.

Though his face was swollen and disfigured, she saw it was the same person who'd put her husband's life back on track - Howard Porter, her husband's former probation officer.

"If it hadn't been for Howard," the woman would tell Porter's wife Theresa Neal, "I'm not certain which direction my husband would have gone."

This man who straightened lives through the telling of his own journey from poverty and the segregated South to college triumphs and voided records, through the highs and lows of professional basketball, and finally to his epic battle with drug addiction and recovery, would never regain consciousness.

A week later, on May 26 of this year, Howard Porter, 58, quietly passed away.

Police don't know who savagely pummeled the 6-foot-8 former Villanovan considered among the best to have played college basketball in Philadelphia - or, more important, why.

***

When Howard Porter first arrived at Villanova in the fall of 1967, students began calling him Howie.

The Main Line campus was all male at the time, and many considered the school of 1,300 a Catholic version of Ivy League, like Georgetown - maybe not Princeton or Brown, but close.

There was status in being a Villanova Wildcat, especially in Philadelphia, and that feeling permeated all aspects of college life - doubly so if you were a member of the track or basketball teams.

The track stars had a cult status all their own, but with hoop stars like Johnny Jones, Bill Melchionni and Fran O'Hanlon, Villanova basketball had become nationally known. Philly rivals La Salle and Temple had been to the Final Four, however, and the pressure from Villanova's alumni to accomplish the same was fierce.

Recruiter George Raveling, an assistant coach and an early African-American college basketball role model, scoured the country to find the best players he could.

His attention turned to Howard Porter, a name he got from a local sportswriter who'd moved to Florida and seen him play.

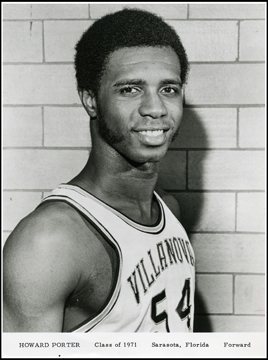

Porter had averaged 35 points a game his senior year at Booker High School in Sarasota. His team won all their 32 contests that season, averaging 102 points a game and earning a state championship.

Every basketball program in the country wanted Porter. Adolph Rupp, the legendary coach who allegedly refused to allow African-Americans on his team, wanted Porter to be the first black player at Kentucky.

Porter could've gone anywhere. He chose Villanova.

***

In an era when freshmen couldn't suit up for varsity, Porter averaged 30 points and twice scored 50 for Nova's freshman squad. But he was still trying to get acclimated to life at a white school in a wealthy tree-lined suburb.

"The name 'Howie' just cracked him up," says former teammate Clarence Smith. "He was never a Howie."

The nickname made Porter an equal of sorts on campus. There were only a few dozen black students at Villanova, many of whom were there to play on the sports teams, and the name Howie provided an ironic twist.

Soon, though, "Howie" became "Geezer," or simply "The Geez" because he'd leap so high he looked like a geyser (and geyser sounded like Geezer). Others, though, say it was Geezer because Porter looked older and acted wiser than other guys. A third theory goes it came from the Robert V. Geasey trophy bestowed upon the Big Five player of the year, because he'd no doubt win it every year.

"He'd skip the ball off the backboard, put his hand on top of the square, and just drop the ball through the net," says Smith. "Stuff nobody could do."

Porter could sky to 12 or 14 feet. Touching the top of the backboard was routine, and he could do it repeatedly with only two steps.

He had the finesse of a ballerina and could make 20-foot jumpers consistently. When he was a kid his mother gave him a book on shooting by NBA legend Oscar Robertson.

"He absorbed that book, digested it," Smith says. "That rhythm and the way he shot was a carbon copy of the way Robertson shot."

Smith says Porter would "true" his shot, correcting his form till it was perfect. Then he'd shoot it a few more times perfectly to carry him into the game.

Matching his offense - maybe even surpassing it - was his monstrous defense.

"He didn't just block shots," former teammate Ed Hastings says. "He knocked them into the eighth row."

***

Attendance at Penn basketball games was thin in the mid-1950s. On nights when neither Penn nor Villanova was using the Palestra, the arena was dark and cold.

"None of the city schools were drawing," says Bob Paul, Penn's sports information director from 1954 to 1962. Paul went to Temple, St. Joe's, Villanova and La Salle, and all agreed a coordinated effort would be financially smart. "We split the money five ways," says Paul.

The Big Five series was born. City high school stars began choosing local colleges, and the fans followed. Radio announcer Les Keiter was becoming a city institution with such shout-outs as, "In again, out again, Finnegan!" (a ball that ringed the rim) and "A ring-tail Howitzer!" (a long jump shot).

"I'd sit up at night listening to the Big Five on the radio," says Fran O'Hanlon, who grew up in West Philadelphia and graduated from St. Tommy More before playing at Villanova.

Soon Channel 17 began televising Big Five games, and the city series exploded. The crowds became big and raucous, media coverage intensified, and the games were among the most competitive in the country.

"It seemed like every game was settled in the last few seconds," says Al Meltzer, the voice of Big Five basketball from 1964 to 1972. "If one team was expected to win, more times than not they'd lose."

***

Villanova began every season with the freshmen playing the varsity. That's when everyone finally got a good look at sophomore Howard Porter's abilities.

"He was leaping tall buildings to get over people," says Mike Daly, Villanova class of 1972. "It was intimidating and impressive."

Built like a track star, Porter had a thin waist, muscular arms and legs that looked 10 feet long in basketball shorts. He wore striped socks high to his knees, thick kneepads and a slight afro. His wingspan stretched the width of the lane.

When he pulled down rebounds, his legs splayed wide, his right leg often kicking above his opponents' heads. His elbows would thrust out and swing menacingly. When he landed, his face revealed a level of fierceness and determination that could melt stone.

"Once you saw him play for 30 seconds," Daly says, "it was easy to see the guy was extraordinarily special."

***

Meanwhile, at Broad and Olney, a world away from Villanova, another star was rising. Kenny Durrett, a smooth-shooting La Salle sophomore, appeared to glide across the lane and score at will.

La Salle was ranked second in the country with 17 wins and a single loss; Villanova was 16-2 when Porter and Durrett met at the Palestra in February 1969. It would be the first epic battle between the two heroic showstoppers.

"The college equivalent of Bill Russell/Wilt Chamberlain," Meltzer says.

Some 2,000 additional fans squeezed into the Palestra's aisles for the big game.

"I had six or seven people in a broadcasting booth big enough for maybe four people," Meltzer says.

Prepped-out students in button-down shirts chanted from one side of the smoky arena to the other, tossing streamers that caused midgame delays.

The La Salle Explorer - a kid in a gray space suit with an absurdly oversized helmet and white boots - bounced around, taunting Villanova fans, flailing his arms and pointing into the crowd.

On the court, Porter altered every shot La Salle put up. He guarded the lane like a pit bull, scaring anyone who thought of driving to the hoop. Though he shot poorly early, he ended with 21 points to match his 21 rebounds.

Durrett, however, paced La Salle with 20 points and 15 rebounds, and Villanova lost 67-64. If La Salle hadn't been suspended because of recruiting violations, they might've made it to the national championship.

Porter was named All-American his first varsity season, along with Lew Alcindor and Pete Maravich, and he and Durrett would share the Geasey Trophy as the most outstanding players in the Big Five.

***

A photograph of Howard Porter with Kenny Durrett hangs on the basement wall of the unpretentious single-story yellow house the late Villanova star called home in this leafy St. Paul neighborhood.

Memorabilia fills the house, especially the basement, which Theresa Neal, Porter's widow, calls "Howard's House."

"Howard's House" is a shrine to Villanova. There are blue pennants and paperweights, stuffed Wildcat mascots and a logo clock among other souvenirs. Porter had a Villanova license plate, and Neal says he'd wear Villanova sports gear when relaxing.

His reassuring smile appears in pictures in every room of the house - with teammates, accepting plaques, raising his retired jersey.

He treasured his time at Villanova, his wife says. Especially the guys he played with.

"Those are really his friends," she says, "in the deepest meaning of the word."

***

In Howard Porter's time, basketball in Philadelphia was a brotherhood.

The kids who played at local colleges were bound together by city and sport year-round. In summer they'd meet in gyms and playgrounds for pickup games.

Many had local ties - Villanova's Hank Siemontkowski was from North Philly, Temple's Joe Cromer was from South Jersey, St. Joe's Pat McFarland was from Willingboro, and Villanova's Chris Ford was from Atlantic City. Some had played in the city's Public League, others for local Catholic schools. The summer pickup games were intense.

"It was for bragging rights," O'Hanlon says. "Where the rivalries were formed."

Basketball was religion - Tuesday nights at St. Joe's, Wednesdays at Villanova and Thursdays at La Salle. Pickup games were played at the Palestra, down the shore and at the city's playgrounds. Herb Magee, Philadelphia University's longtime head coach who worked at a swim club in Drexel Hill with Jimmy Lynam, would open the club's courts on Sundays.

O'Hanlon remembers taking Porter to his home court at 58th and Kingsessing, and watching him put on a show for the neighborhood.

Friendships endowed regular-season games with special meaning.

"Because you knew each other," says Daly. "It's not like they were from Indiana and you never saw them before."

The fraternity fostered a Philadelphia vs. the world mentality.

At the University of Kansas in 1970 some Kansas fans started snapping at the St. Joe's Hawk mascot flapping his wings.

Porter, whose Villanova team was also in the tournament, walked over to the student in the Hawk costume. "I'll make sure nobody messes with you," he told him.

***

Howard Porter was an All-American again his junior year, and despite having only nine players due to injuries, Villanova was among the top teams in the country his senior year.

Injuries had depleted the bench, so they had to suit up their team manager Larry Morgan just to round out practices. It made the bond among the players even stronger.

The team was ranked fourth in the nation as they headed into the winter break in 1970. Then came a disastrous tournament trip to Hawaii, where they lost back-to-back games against Brigham Young and Michigan, and dropped out of the national rankings.

Shortly after, Porter made a day trip to New York. The evening he left he had a brief conversation with teammate Clarence Smith. Not much was said, Smith says, except at the end Porter waved his hand in the air, making a "Z" as though signing a check.

"I understood immediately what he was talking about," says Smith. Porter was saying he signed a professional contract. "He was telling me because he wanted my opinion."

Smith, who was stunned into silence, knew the consequences and how it might affect the team. He also knew Porter's mother cleaned houses for a living, and his family needed money.

He didn't know Porter had already hired an agent before the Hawaii trip.

"I wish to this day that I'd said something," Smith says.

Porter's contract remained a secret through the team's magical 23-6 season. They cruised past St. Joe's and Fordham in the first two rounds of the 1971 NCAA tournament, and they crushed Penn - ranked third in the country with a 28-0 record - in the east regional final, 90-47.

They defeated Western Kentucky in double overtime and advanced to the national title game, where John Wooden's UCLA, winners of the previous four titles, waited.

Porter played magnificently in that game, scoring 25 points and pulling down eight boards. But it wasn't enough. UCLA rolled to its fifth consecutive title with a 68-62 victory.

Though Porter was voted the game's most outstanding player, he never saw his trophy. After the game the NCAA declared Porter ineligible, and voided the majority of the 1970-'71 season, dating back to the day Porter contracted an agent.

"The money was there," Porter told Sports Illustrated in 1996, "and I'd never had money."

***

The contract Porter signed with the ABA's Pittsburgh Condors was sold to the Chicago Bulls in 1971. He was given a five-year deal worth $1.5 million, huge money in those days.

But he never became the star he'd been in college.

At Villanova Porter didn't have to change his back-to-the-basket offense or put the ball on the floor. The guards would find him, and he'd simply turn and shoot.

But in the NBA nearly everyone played at Porter's level, and some on a higher plane. He played on four different teams over seven years before quietly retiring in 1978, after a blood clot was found in his lung.

"He felt responsible," says Meltzer of Porter's troubles at Villanova. "That had an enormous effect on him when he went into the pros."

Porter - by then a father of three - returned to Florida. He'd retreated from his college friends after the 1971 season, and with his basketball career over, he turned to cocaine.

"If you feel bad about yourself, you find a way to medicate yourself," Porter said in 1996, 25 years after his team's championship run. "My medication was cocaine."

Having lost the '80s to drugs, Porter went to the Hazelden Clinic in Minnesota to clean up. After a 28-day treatment in 1989, he was offered a job with a treatment program, counseling recovering addicts.

He still felt bad about his college career, friends say, but he had a home in Minnesota with a job helping people and a woman he loved.

***

In 1995, shortly before he married Theresa Neal, Porter went to work as a probation officer.

"He never, ever hid behind his struggles," Neal says. "He used it as testimony. Howard, to this day, would say, 'I'm never trying to minimize the despair.'"

He counseled murderers and forgers, drug dealers, spouse abusers and thieves, all of whom would face serious time if they were busted again. His clients were mandated to see him several times a month in his St. Paul office. His reputation grew.

He received cards from prisoners. "I hear you are a great probation officer," they'd read. "Is there any way I can work with you?"

The towering man with the omnipresent smile sported slick suits, often three-piece, with eye-catching ties and a fedora - always a fedora.

"He came from very little means, but being well dressed was something his grandfather instilled in him," Neal says. "It was important to his mother and grandfather."

He became a role model for clients, a heroic figure, a magnet. He couldn't walk from his office, down the long corridor to the bathroom, without being stopped by friends and acquaintances.

"Other people's clients would stop him just to talk or ask advice," says Rhonda Rhoades, Porter's supervisor.

Few in the community knew that Porter had starred at Villanova and played in the NBA.

"It surprised people," says Chris Crutchfield, deputy director of community relations and external affairs. "We knew him on the strength of his character."

***

On June 2 nearly 2,000 people - including former Villanova teammates, NBA players and local politicians - attended funeral services in St. Paul. The line into the church ran nonstop for more than three hours.

"You'd expect that of a Dave Winfield or Kirby Puckett," says Crutchfield, referring to two local icons. "It was absolutely packed. It knocked you over, the energy people showed."

One former probation client rode the bus for three hours to pay his respects. Clients cried as they walked down the aisle, and many stopped by Porter's home afterward to hug Theresa.

"He made an impact on the basketball court with his athleticism," Neal says. "He made an impact on the community with his spirit."

***

The services for Porter brought the brotherhood back together.

Several colleagues and opponents from that era now coach in the Philadelphia area. There are reunions and gatherings, and the players often show up at each other's games.

"The guys I played basketball with were the greatest guys I've met in my lifetime," says Villanova teammate John Fox, who now lives in Minnesota. "There's a special bond."

Porter himself had become a regular guest on the Main Line campus ever since Villanova retired his jersey in 1997. In 2006 he was honored as the second-best player in Big Five history, behind Kenny Durrett, his old nemesis.

The city series has undergone great changes in the years since Porter and Durrett ruled the courts. Large conferences pulled teams away, and recruiting and the NCAA tournament became big business.

Now there are only a handful of games between city rivals every year. The players come from around the world, and the fans aren't invested like they were when the players were from Roman and Bonner and West Philadelphia High.

The Porter-era guys long for the halcyon days of Philadelphia basketball.

"You could run through that locker room door without opening it," says Tom Inglesby. "The adrenaline was just incredible. You had to be there."

***

Villanova's Mike Daly and Joe McDowell, two guys who were there, flew to St. Paul to attend Porter's funeral.

The day before, they caught up with old teammate John Fox, and the three went to the alley where the Geez was found beaten.

"Everybody told me, 'Don't go,'" says Daly.

But on a beautiful late spring day in the Midwest, they went anyway. When they found the location, these three white men in suits stepped out of the car and wandered around.

"It was hard to imagine a guy of his size lying there helpless, somebody doing that to him," Daly says.

Neighbors came out and spoke to the men, told them what they knew and expressed their sympathies.

"I don't know how I felt when I left," Daly says, "but I was glad I went."

Daly also attended services for Porter on the Main Line, and the burial in Orlando, where Porter was interred alongside his mother and brother.

"I'm still struggling as to who would want to hurt Howard," his widow says. "He was gentle in nature and in spirit. He was kindhearted. He would give before he would take. He was convicted in his faith. He was convicted in his beliefs. His struggle ... He was never ... "

Her voice trails into silence.

***

"We brought two people into custody, but didn't have sufficient evidence to charge them," says Tom Walsh, information officer for the St. Paul Police Department. "They continue to be people of interest."

Walsh says he's confident the case will be resolved.

Neither of the suspects was a probation client of Porter's. One brought into custody was a 33-year-old woman, 5-foot-2, 135 pounds, about half Porter's weight.

Neighbors who live near the alley where Porter was found want answers.

"People say police did it," says Theresa Cloud, a mother of six whose home backs onto the alley. "Who else could have kidnapped and beat him? They solve every other murder, right?"

***

A few days after Porter's body was discovered, Tom Inglesby called former teammate Clarence Smith with the news.

"It doesn't look like the Geez is going to make it," he said.

Smith couldn't sleep after learning of Porter's beating. He feared the Geez had fallen back into drugs, and that old demons had led him down the path of destruction.

"I was concerned for his immortal soul," Smith says.

Smith tossed and turned in bed so much his wife finally snapped, "What are you doing?"

Then, on the night Porter passed away, Smith had a vision.

"I was talking to Howard, and I realized this was not a dream," he says. "It was a visitation."

The tender, well-dressed Porter approached Smith and said in his lingering Florida accent, "You're taking this all too hard."

Smith says it was unmistakably the deep voice and sentiment of Howard Porter.

"You're taking this all too hard," he said again.

"He was comforting me," Smith says. "And all the questions I had about Howard making it to the next level were answered."