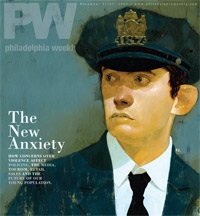

Proceeding With Caution

The men in blue ponder the new realities of violence against police.

From the November 21, 2007 Philadelphia Weekly

As soon as the call came in last Tuesday evening, dozens - maybe hundreds - of police officers sped to the scene in Frankford.

"Shots fired, officer down" - dreaded words that have become all too common here in recent weeks; words that signify, some believe, a deeper horror in the city.

"Shooting a police officer is more than a crime against an individual," Inspector Joe Sullivan says. "If we're not safe, you're not safe. This is a crime against all of us, the whole city."

In the span of two months six officers have been shot while on duty, including 25-year veteran Chuck Cassidy, who was murdered - shot in the head at close range - while trying to break up a robbery at a Dunkin' Donuts in West Oak Lane. A traffic cop was shot in the shoulder while chasing a suspect down Sansom Street in Center City. A patrol officer was blasted in the face by a gun-wielding thug in West Philly.

Last week two officers were shot while serving a warrant. The alleged shooter is 16 years old.

"When I came on the job, people were basically afraid of shooting cops because of the ramifications," says Sullivan, a 25-year veteran and supervisor at the Northwest Patrol Division where Cassidy was stationed. "People aren't afraid anymore. I'm very fortunate to be where I am because I'm not sure I'd want to be a cop on the street right now."

Police patrol in a heightened state of alertness, and criminals seemingly dismiss the uniform as just another obstacle - last Wednesday two officers were nearly run over by a band of alleged carjackers in a stolen SUV.

"There is definitely anger and frustration in the department," says Chief Inspector Keith Sadler, chief of detectives. "The only thing that has made it easier has been the overwhelming support of the community. I can't express how crucial that is to our guys on the street."

Flowers and cards continue to arrive at Cassidy's patrol station. A group of school children delivered chocolate-covered pretzels last week. City residents lined the streets in silence as Cassidy's funeral procession wheeled by two weeks ago. Donations for the family have steadily rolled in, and an anonymous donor has agreed to pay the education expenses for the three Cassidy children.

Following Cassidy's murder, police received more than 200 solid leads from the community.

Sadler, who was among the internal favorites to succeed Sylvester Johnson as commissioner, deflects critics who say police were more aggressive in their manhunt because this victim was one of their own.

"Normally, we're working with nothing," he says. "If there's no information, no leads to follow, we're limited in what we can do."

Sadler says it may be hard to get upset when criminals kill each other, but, "We don't have the luxury of saying, 'He's a killer. We won't investigate.' We investigate everything. But we get no cooperation."

But the spate of police shootings has created a sense of unity with the community - if the police are targeted, anyone can become a victim.

"When the criminals are shooting at each other, there's a sense of urgency," says John McNesby, president of the local Fraternal Order of Police (FOP). "When they're shooting at uniformed police officers, it's a whole different level. We all have the common goal of watching each other's backs."

After officer Richard DeCoatsworth was shot in the face in West Philadelphia, police received dozens of leads on the alleged shooter. The Citizens' Crime Commission, which operates an anonymous tip line (215.546.TIPS), reports that tips on all crimes have increased in recent weeks.

"There's now a greater level of understanding that our civilian occupation is very dangerous," says Capt. Daniel Castro of the Command Inspection unit.

There's no such thing as a routine call. Any situation has the potential to explode, Castro notes. Cops put their lives at risk every time they hit the street.

"You wouldn't do that for $1 million," he says, "but every day in Philadelphia, we do it. And for far less than $1 million."

The recruitment of new officers nationwide is difficult because of the high risk and low starting salaries, not to mention historical mistrust of police from some communities. Chief Inspector Sadler remembers when he took the police exam in 1980, there were nearly 25,000 people taking the test at 15 locations. At the most recent exam only 3,000 people tested.

The murder of Cassidy, a popular officer who passionately served his childhood neighborhood and never sought the limelight, isn't likely to encourage people to join the force. But his death, along with the other recent police tragedies, may create a positive effect - at least temporarily.

"We seem to dwell on the things that divide us," says Inspector Sullivan, who graduated from the police academy with Cassidy. "Now I think we're starting to define ourselves as people who respect the law and people who don't, instead of by race or status, us against them."