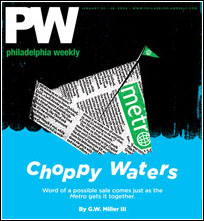

Pushing Paper

Amid a flurry of sale rumors, Philly's Metro turns 8. Will the free daily make it to the decade mark?

From the January 23, 2008 Philadelphia Weekly

"Come on, people!" Brenda Bowens barks. "Shake a leg. It's a happy Monday!"

An army of bundled-up, coffee-carrying, blank-faced drones trudges across Market Street near 15th at 8 a.m. with few people glancing at Bowens despite her bright orange jacket and ridiculously merry smile.

She doesn't give up.

"Let's rock 'n' roll!" she orders. "It's time to make the donuts!"

A "brand ambassador" for the Metro, Bowens waves copies of the free daily newspaper in the air, offering them to people who are rushing to work, waiting for the bus or running to catch a class.

But Bowens is more than just a street hawker. She can be a life counselor, comedian and sometimes even a friend to the anonymous.

"You got a paper already, baby?" she sassily asks a heavyset man in a black leather coat standing in line for the bus.

The man looks down and smiles sheepishly.

"Ah-huh," Bowens grunts. "You're cheating on me!"

She pivots to deliver more papers, to hug more morning regulars, to wave to more SEPTA drivers. She belts out more encouraging words, drops stacks of papers on buses, cracks jokes and even offers directions. She flags down a bus that tries to drive off as a wannabe-rider runs with her arms flailing in the air.

"I want to see them smiles today!" Bowens bellows to no one in particular while constantly bouncing, twirling, running and teasing like she does here every business day.

Her laughter and spirit are contagious, and soon a crowd gathers around her. They're lively and laughing and talking about the photo of Terrell Owens crying on the front of the Metro.

When 3-year-old Jalin Elias sees Bowens, he raises his little arms in the air and runs toward her.

"How you doing, darling?" Bowens says as she lifts the smiling boy in the air.

They spin while Bowens holds Jalin to her chest.

"He looks forward to seeing her every day," says Jalin's mother Ann-Marie Elias. "If he doesn't see her, he gets all upset."

***

Like Bowens, the Metro has become a part of many Philadelphians' morning routine - an easily digestible 20-minute introduction to what's going on in the city and around the world.

The Metro that's produced by 11 full-time editorial staffers today isn't the newspaper for the working-class masses that launched eight years ago this week.

The Metro is actually cool.

Or at least it tries to be.

Over the last two years the Metro quietly reinvented itself as a daily niche publication attempting to reach young Philadelphians through stories about indie bands, the future of the city, pseudo-mayoral candidates with mohawks and the anticasino movement. They even published a front-page story about a New Year's Eve party that ran out of alcohol and another about a clash between crusty punks and police at the First Unitarian Church.

"The Inquirer doesn't care about stuff like that," says 30-year-old Metro editor Ron Varrial. "Who'd have thought a daily newspaper would put a story like that on the front page?"

With the new emphasis, circulation increased nearly 10 percent, bloggers wrote about their coverage, and Philadelphia magazine even recognized the Metro's political reporting in its best-of issue.

The Metro, which has had numerous iterations over its brief lifespan, seemed to be finding its way.

But with the news last week that the three U.S.-based Metro papers (in New York and Boston, as well as Philadelphia) may be sold off by their Luxembourg-based, Swedish-bred parent company, is all this transformation coming too late?

If so it would be a shame. The Metro has survived a lawsuit, a massive blizzard, staff upheavals, a divorce from its major partner, a revolving door of editors and publishers, the growth of the Internet, a steep circulation drop and biting criticism from longtime journalists about the superficiality of its content.

But the paper is bleeding money, and some say the Metro's core audience - public transit commuters - isn't the niche its editorial content is trying so hard to reach.

***

If you've made it this far into this story, you've already defied conventional wisdom that says young people won't dedicate time to read long stories in newspapers. Many in publishing believe the Facebook generation is unable to focus on a full daily edition of The New York Times or The Washington Post.

"There's just so much competition for their attention," says Philip Meyer, a University of North Carolina journalism professor and author of The Vanishing Newspaper: Saving Journalism in the Information Age.

These so-called experts think you, young readers, have attention deficit disorder, and that writers had better inform you quickly and briefly before you drift off and start thinking about video games, YouTube or that Chicken McNuggets song.

Enter the Metro. You could've read four or five bite-sized Metro stories in the time it took you to get this far. The average Metro article runs fewer than 250 words, and some are as brief as 50. (A Terrell Owens cover story ran 58 words.)

"There was a time when people could devote several hours to reading the paper," says Metro publisher Eric Mayberry. "People don't have that luxury anymore. We're letting the market decide how they want their news."

From the end of 2006 through last September the Metro's total average circulation increased by 12,343 copies daily in an era when most daily newspapers are losing readers faster than the Sixers blow early leads.

The Metro now delivers an average of 139,388 free copies Monday through Friday. At an estimated 2.2 readers per copy, it has a total daily readership around 300,000. The Inquirer's paid circulation for the same period is around 338,000 daily, and roughly 662,000 on Sundays. The Daily News sells around 112,000 papers a day. (Before the Metro launched in 2000, Daily News circulation was about 162,000.)

The paid dailies argue that a free daily newspaper can't offer the same quality of information they can.

"I don't think being a free paper devalues the product," says Mayberry, a linebacker-sized, bowtie-wearing 41-year-old Wharton grad who was the former director of advertising for the Daily News before joining the Metro in December 2005. "People don't care. They say, 'I want to know what's going on, but why should I pay 60 cents?'"

(Last Friday the Metro reported that the Inquirer and Daily News will be raising their single copy price to 75 cents.)

Mayberry says he doesn't consider paid dailies competition. He believes most Metro readers wouldn't bother reading the Inquirer or Daily News either because they don't want to pay for the news, they feel disconnected from the content, or they get most of their information from niche sources on the Internet.

Instead the Metro is trying to get its product in the hands of the "right people" - i.e., the influential youth market.

"The reason this all works is because of Ron," Mayberry says, referring to the Metro's editor for the last two years. "Ron just gets it. He knows how to speak to our targeted demo."

***

Ten Metro staffers sit around the large conference table in a room with blank white walls on the 14th floor of 30 S. 15th St. In December they moved into this office space - which is about double the size of their old location on the ninth floor - and they haven't decorated yet. A framed print sits sideways on the carpet.

Varrial looks around the room full of predominantly fresh, young faces, and asks, "Does anyone have Nutter fatigue?"

Everyone groans their assent. One week into Michael Nutter's mayoral tenure, and he's already played out. The staff quickly moves on in search of what could become the lead story for tomorrow's cover.

The options are slim. There's a bar-hopping feature on Steve Odabashian, a piano-playing Andy Reid impersonator, and another about a hip-hop and hookah party at Byblos restaurant. The city's new top cop is making neighborhood visits, and the ping-pong Olympic trials are in town for the weekend.

"Adam took on one of the ladies, and she whupped him big time," says sports editor Jordan Raanan of writer Adam Levitan who's standing right behind him.

Night news editor Josh Cornfield has a pitch.

"I think this could be a good one for our people," he says. "Innovation Philadelphia. It was a John Street pet project supported by $2.5 million from the city. We're looking into whether Nutter will keep funding it."

"I noticed every page today feels like it has Nutter on it," says editor Varrial in his fast-talking Jersey accent.

"And he probably hasn't even unpacked yet," says copy editor Jody McClain.

Varrial ends the brief session without reaching a decision, and then announces, "Of everything we've tossed out here, nothing's really getting my juices flowing."

***

The Metro first published in Stockholm in 1995, and within a few years there were editions in Prague, Budapest, Helsinki and several other European cities with well-used transit systems that carry commuters to downtown areas.

The Swedes decided to make Philadelphia their first operation in the United States in large part because they'd made an arrangement with SEPTA, which has 350 million riders annually. The Metro would be distributed at more than 850 locations in and around train stations and bus stops, and stacks of papers would be left on buses and trains.

Three days before the Metro first hit Philadelphia streets, the publishers of The Philadelphia Inquirer and Daily News, along with lawyers for USA Today and The New York Times, filed a lawsuit claiming the Metro's partnership with SEPTA created an unfair advantage because the paper would be made available where the other publications couldn't distribute.

"That kind of shows where their head was at," says Jack Roberts, the Philly Metro's original publisher. "They weren't interested in innovation. They were interested in protecting the monopoly in their markets."

Then, on the second day they published here, 10 inches of snow blanketed the city, shutting down schools and offices and even much of the transit system. The power in the Metro's Broad Street office went out, and they moved the staff - including visiting Swedes from corporate headquarters - to temporary facilities in the Courtyard Marriott near City Hall.

"For starting a daily newspaper," says former publisher Roberts, "it was the worst nightmare you could think of, between the lawsuit and the snowstorm."

Because of the lawsuit and its new daily newspaper business model (free!), word of the Metro spread, and dozens of brand ambassadors like Brenda Bowens were recruited to put the paper in the hands of Philadelphians every day.

"Within two months our market knew we existed," says Roberts. "Within three or four months we had a market that really considered the paper its own."

By the end of its first year circulation hovered around 138,000, with estimated readership around 443,000. The paper brought in $3.6 million in sales revenue during its first year. But the operation lost $8.8 million overall, much of it due to startup costs.

***

The newspaper industry, which had suffered declining readership for more than a decade, and was facing serious advertising revenue declines, watched the Metro closely.

A free daily newspaper could erode a traditional daily's circulation even further, and nobody needed that. In a defensive move, several big-city dailies - the Chicago Tribune, The Washington Post and The Dallas Morning News, among others - created free versions of their paper. By 2005 more than a dozen free daily papers had been launched across the country, each mimicking the Metro formula - brief summary stories in a colorful tabloid format.

The Metro knockoffs were criticized internally as journalistically light, a glorified vehicle for ads. Many longtime journalists scoffed when asked about the free dailies. Most didn't consider the papers journalistic competition then - and they still don't.

"I can't say there's a lot of conversation about the Metro here," says Daily News editor Michael Days. "On any given day 90 percent of the papers we sell are sold on the street. So people are willing to go in their pocket and take out 60 cents. You're not going to get the varied voices we offer in a free paper. Not in this market."

The Daily News itself worked on a free-paper prototype called Sizzle for more than a year before Knight Ridder, then its parent company, pulled the plug in 2005. The much-maligned project - bringing up Sizzle to Daily News editorial staffers still elicits shaking heads and rolling eyes - was one of Eric Mayberry's final assignments before the Metro hired him.

"Being free isn't bad, but being thin on content is," says journalism professor Philip Meyer. "Free newspapers? They might be the saviors of print journalism."

***

"We broke stories," says Andrew Busch, one of the Metro's two original reporters. "We generated a lot of original features."

Busch was the first journalist to report that Philadelphia would be a venue for Live 8, the massive worldwide concert event.

But the news cycle quickly overwhelmed the small staff that also had to frequently edit copy, proofread pages, shoot pictures, help with budgeting and even lay out pages. They tried to cover local events, but wire stories filled most of the paper.

In 2004 the Metro started pushing for stronger local coverage.

"The reporters knew that if they did a good local story, it would go out front," says former news editor Eric Fisher. "That didn't happen before."

The change spurred the staff to work even harder, and it brought results. The Metro averaged 143,000 papers a day that year, slightly topping the Daily News, which remained at 141,000. And after four years in business, the paper finally became profitable. During the Eagles' run for the Super Bowl in 2005, there were days when circulation topped 170,000.

But around that same time the New York Metro was created, and some duties, like page layout and copy editing, were centralized there. The Manhattan office began to edit Philly stories and even write Philly headlines.

When editorial decisions started coming out of New York, frustrated Philadelphia staffers started leaving the paper.

"New York felt we had too many crime stories, and that ongoing violence wasn't really a big story in Philadelphia," says Chris Baud, who did stints as news, entertainment and sports editor during his three years at the Metro. "It's hard to imagine what could be more important to Philadelphia readers than the chronicling of its horrific crime problem."

One of the most infuriating days for Baud came on Jan. 21, 2005, when the New York office decided to run a large photo of George Bush dancing at his inauguration party on the cover. That same weekend, the Eagles were playing in the NFC championship game.

"We were told to make the paper interesting to professional 28-year-old women," Baud remembers.

In May 2005 circulation reached an all-time high, averaging more than 160,000 copies daily. But morale was low, mistakes were frequently published, and a downward spiral began. Circulation declined to around 120,000. Then the paper severed its ties with SEPTA, making distribution that much more difficult.

When Ron Varrial, who had been sports editor at the New York Metro when it launched, arrived in Philadelphia to become news editor in June 2005, the remainder of the original Metro staff vacated. It wasn't coincidental.

"When I got here, newsgathering was sitting down to watch the 5 o'clock news," Varrial says. "All you had to do was watch the news at night to know what was going to be in our paper the next day."

(For the record, every former Metro staffer interviewed for this story denies they simply rewrote TV news stories).

The Metro didn't have the staff to be comprehensive or become the paper of record. So Varrial directed his personally assembled staff to stay away from reacting to breaking news and to focus instead on issues and trends.

"Just because it happens doesn't mean it's news," he told them. "We're supposed to be the anti-newspaper."

Forget the stories about retirement, the police blotter or the evening's TV lineup. He told his staff to quit writing about who's going to win American Idol and instead write about the acts that were going to appear at Johnny Brenda's.

"We have news in the paper so readers can do well in quizzo," jokes entertainment editor Dorothy Robinson. "But they also have to know what's going on in Philly. I kind of think of my section as a cheerleader for the city."

The newsroom has the energized atmosphere of a college newspaper.

"What unifies everybody is that they get it," Varrial says of his staff.

***

But two weeks ago a report citing an unnamed Metro executive surfaced that the papers in Boston, New York and Philly were up for sale. This came on the heels of year-end reports that the Metro brass were reviewing the performances of their holdings.

Now the newsroom that finally gelled over the last two years is sweating.

"To my knowledge, we are not now nor ever were targeted for sale," says Metro publisher Mayberry.

(The newspaper company that was rumored to be the Metro's buyer, Clarity Media Group, has denied any interest in the papers.)

Mayberry suggests the confusion may have stemmed from the fact that the parent company is looking to expand its U.S. operations and is seeking partnerships like it has in Boston, where The Boston Globe owns a 49 percent stake of the Boston Metro.

***

The hard reality, though, is that advertising sales dropped 5 percent in Philadelphia during the third quarter of 2007 alone. Sales overall for the year were flat, although the Metro won't provide definitive figures.

The paper draws more entertainment advertising now, but it still doesn't grab the high-end retailers. Instead readers are offered used-car dealers, fast-cash-now joints and the Tru-Tone Hearing Aid Center. It seems the Metro can't shake its reputation as the medium for the mass transit crowd.

"A free, general daily newspaper is kind of an anachronism because it's not very niche-y," says Ken Doctor, former head of Knight Ridder Digital who now consults news organizations about new technology. "By nature it's general. It's print. What's working is targeted and niche, not general and mass. The world doesn't want mass media at this point."

During the first nine months of last year the Metro's parent company, which operates 83 free daily newspapers in 23 countries, reported a net loss of $32.7 million. More than $9 million of that came from the three American papers.

***

"Come on, sugar, you can do it!" Metro hawker Brenda Bowens belts out to a jaywalking woman hustling to avoid oncoming traffic.

By 8:45 a.m. Bowens' stack of newspapers is all the way down to her knees. When she arrived at 5:45, there were two stacks that were both nearly as tall as her 5-foot-2-inch frame. That means Bowens has handed out around 2,000 copies so far.

And each paper comes with a glorious and infectious grin.

"She does a wonderful job," says Antoinette Waymer, a mother of four who girl-talks with Bowens every morning for 20 minutes before catching a transfer to Conshohocken.

"She keeps this corner smiling. If they take her off this corner," Waymer says, "I don't know what I'm going to do."

UPDATE FROM JANUARY 30, 2008: No sale yet, but two editorial staffers released.