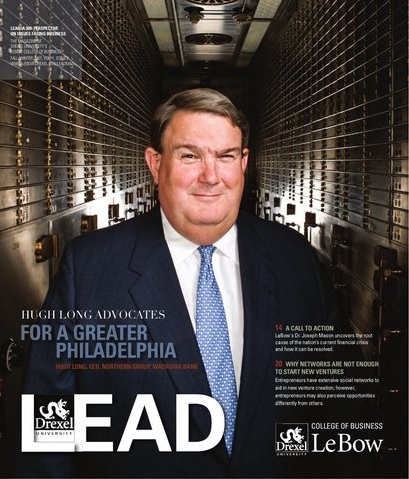

A Call to Action

Joseph Mason knows the financial crisis is deeper than just a sub-prime lending problem. But no one seems to be doing anything about it.

Published in the Fall/ Winter 2007 issue of LEAD magazine, a publication of the LeBow College of Business at Drexel University.

Houses were being constructed all over the country at a rapid clip and competition for loans was fierce as Joseph Mason was compiling research about mortgage-backed securities and collateralized debt obligation last year.

The housing market had never been hotter - the condo boom was surging in Philadelphia and housing prices across the country were 84 percent higher than ten years earlier. It wasn't just prices increasing - the size of newly built homes was expanding annually. The average single-family home was pushing 2,500 square feet, nearly 800 square feet larger than the average 30 years prior.

And despite the ongoing war in the Middle East, the American economy was cruising along with the Dow Jones index rocketing to unprecedented highs.

Things seemed grand.

While the rest of the financial world watched stock prices rise and portfolios grow, Mason, an Associate Professor of Finance and LeBow Research Fellow, worried that a crisis of global proportions was just around the corner.

He feared that the imminent collapse of the housing market would be just the beginning. There would be more at stake than individual homeowners defaulting on their loans. A meltdown along the lines of the stock market crash of 1929 could be in the very near future.

And nobody seemed to be doing anything to prevent it.

When the mortgage crisis began to wallop the United States last winter - right around the time that Mason's research was published - everyone looked to him as the expert prognosticator, the man who knew what was going on behind the shady lending deals.

He began appearing on Bloomberg television, CNBC and National Public Radio, and he spoke to reporters from around the world. He quietly explained that the sub-prime mortgage crisis wasn't the real issue here even though it was getting all the headlines. This is not simply a matter of bad loans made to the wrong people.

There is an institutional problem that has been growing for more than a decade, he stated. This is a structured finance crisis, and the system of financing has so corrupted the industry that no one knows who owns what anymore.

"The danger is that we take this to a full blown asymmetric information financial crisis," Mason says. "You want an example of an asymmetric information financial crisis? You can look at the Great Depression."

He is telling everyone he can that something needs to happen - self-regulation needs to be implemented, the government needs to take action, something. Anything.

But it doesn't look good right now.

"Personally, I don't think we want to let it get this far," he says. "I have my doubts that people are wise enough not to let it get that far."

***

"I'd like to say that I called it but the timing just worked in my favor," jokes Mason, who co-authored the February report with Joshua Rosner, managing director of the independent financial services research firm Graham Fisher & Co.

"It's exactly the type of thing that you wish you weren't right about," says Rosner with a chuckle.

Mason had been studying collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) rather quietly for more than 12 years, ever since he was a financial economist in the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, which regulates nationally chartered banks to ensure safety and soundness.

"I thought it was an important sector, about twice the size of the municipal debt sector," he says. "Now it funds over 70 percent of all consumer lending."

He saw mortgage-backed securities as a very powerful tool that banks were using to skate regulatory requirements. It was something that was ill understood and not being reported to or monitored by regulators. The logic behind the lack of transparency was that there was no reason to monitor these transactions because the claims were being sold to markets rather than residing in banks.

"So few people even knew what it was and yet it was one of the darlings of Wall Street," Mason says.

He watched as the mortgage-backed securities and collateralized debt obligation markets became the Wild West - virtually unregulated.

Mason knew the housing bubble and mortgage industry were due to tumble, but they weren't the real issues. This wasn't a temporary setback in the credit card sector, a hiccup on the national radar. This was about people's homes, and it impacted banks, financers, investors, brokers and everyone else involved in getting deals done.

"Before February, hardly anybody knew what structured finance was," Mason says of the month his research was released. "Now, of course, its all over the headlines."

***

Creative financial engineering is what caused the current sub-prime mortgage-lending crisis and if the situation is not studied and amended, a massive economic collapse could come, Mason says.

It starts when a broker pools together a large number of mortgages. An investor will purchase the pool of loans, raising money by selling securities. The securities, however, are little more than claims to the cash flow created by the pool of mortgages - mortgage-backed securities.

Good loans are easy to sell but the risky ones are orphaned. Some equity pieces are so bad that they represent almost assured loss.

"Who's going to buy them?" Mason asks. "If the bank holds them, they have to keep them on their balance sheet. So they really, really, really want to sell them."

The riskier mortgages get lumped together in CDOs which are then resecuritized until they become sellable.

"CDOs became the favorite home for these higher risk investments," Mason says. "When you create the CDOs however, you have a similar set of trounced securities that you're selling to markets which results in a similar set of highly risky securities at the bottom of the waterfall that you need to sell. Then you create the CDO squared and put those in again. You can keep going through these reiterations but the fact of the matter is there's no long term happy home for these securities, like pension fund investors, who would like to sit on them for 30 years."

The risk keeps getting shuffled around and around, repeatedly brushed under the carpet until it is so hidden that no one realizes its there.

***

The current crisis can be traced back to the inflation era of the 1970's and, specifically, the failures of Franklin National Bank in 1974 and First Pennsylvania Bank in 1980. The collapses of those two institutions showed that even relatively large banks were vulnerable.

When other banks subsequently failed and economies tanked, the world fell into recession.

The issue was that banks had little capital - the equity capital-to-assets ratio at the largest bank holding companies reached a low of 4 percent in 1982 - and the recession only made the situation more precarious.

The central bank governors of the Group of Ten countries adopted the Basel Accord in 1988, establishing a standardized minimum ratio of regulatory capital-to-total risk-weighted assets of at least 8 percent.

US regulatory requirements were implemented in 1991 based upon the original Basel Accord.

"Banks found it hard to sell their stock in order to accumulate retained earnings in order to raise capital - the numerator of that ratio," Mason says. "Therefore they sought other ways to decrease the size of the denominator - rather than increase the numerator - and sell assets in order to make that ratio meet regulatory requirements."

At that time, securitization had been around for more than a decade and it seemed like a handy way to manipulate the variable. For the most part, it worked: it reduced bank capital ratios.

"Was it the cause of this crisis?" Mason asks rhetorically. "Yes, it most definitely was."

In the short run, world economies slowly improved and the recession passed. But the new strategy also created a monstrous demand for mortgage-backed products, which in turn created the rise of the risky sub-prime lending industry. On a dollar volume basis, the sub-prime lending industry has gone from $35 billion in 1994 to $625 billion in 2005, Mason and Rosner reported in their study.

In recent years, home ownership reached record highs and the competition for lending deals has become intense.

To increase the pool of mortgages that could be securitized, more and more deals had to be made. The lenders shifted their priorities from finding borrowers who could repay principal and interest over the life of a loan, to simply finding borrowers who could repay interest. Lenders began carrying significantly higher leverage: 38 percent of all sub-prime mortgage originations in 2006 were for 100 percent of the value of the home, Mason and Rosner reported.

"The strategy's still working in a perverse sense for the banks," Mason says. "So far the assets haven't come back to the banks although that is under discussion today."

In other words, the losses, for the most part, have yet to be revealed. We haven't yet seen how deep the problem is.

***

"When we saw the sector fall apart, what did we see?" Mason asks. "First we saw warehouse lines go. Banks were reluctant to provide brokers more warehouse lines because they didn't need the new loans being produced because they couldn't securitize those new loans. At that point, the banks needed to fund the loans on their own balance sheets or find some commercial paper to tide them over. For the first few months, it was OK - from February to August, roughly six months. Then the commercial paper market broke - in particular, the asset-backed commercial paper market. And so you had a breakdown of funding all along the spectrum - from the warehouse line of credit through the commercial paper market to the securitizations to the CDOs and to the hedge funds."

As the number of defaults continues to rise - and experts predict 2008 will see an even higher rate of defaults, it becomes obvious how these deals became mis-engineered, Mason says. It's a complete breakdown of the financing system, and it's not isolated to one sector.

"Inflation is already taking bite," he says. "Internationally, the dollar is plummeting compared to other currencies. This is a direct connection to this crisis."

Risky structured finance securities, many with assured losses, are now held in various places - pension funds, mutual funds, banks and elsewhere. With no one certain who holds what and with assets hidden deep within sketchy documentation, the full force of the crisis may still be on the horizon.

"Until investors can figure out who holds what, they're not going to get back into the market," Mason cautions. "Well, they might get back into the market without knowing who knows what but then the situation will just get worse."

Rosner agrees: "Investors are saying they don't have enough available information to rationally assess the risk so they're going to go on a buyer strike."

***

"There's a lot of banks, hedge funds and pension managers and investors who are still sitting on considerable levels of losses," Rosner says. "And they're being very slow, and in many cases, continuing to play games to try to hide those losses."

He notes that the Japanese banking problem of the 1990's became a crisis after banks tried to hide their losses. That crisis lasted a decade and is still on the mend.

"We need to have increased standardization of products," says Rosner. "Increased standardization of contracting terms, such as in the pooling and servicing agreements, etc. We need to have increased closure end transparency to investors."

This can begin already, Rosner and Mason agree.

"You don't need the government to tell you to do this," Mason says. "If you are interested in financial stability of the company, you can provide this transparency on your own. The sooner you do so, the smoother your business will be."

The reluctance is that it would be incredibly costly to pour through deals to find out what is being held. The firms don't have the manpower to truly reassess these securities and find where many of the investments lie. And ratings agencies don't have the manpower to go back and re-rate securities.

"The ratings system needs to be anchored in some way," Mason says. "What we have effectively done is to outsource regulation to the ratings agencies. We allowed the ratings agencies to operate on an independent basis without any type of surveillance whatsoever."

***

"We're all to blame," Mason says.

Brokers engaged in fraudulent lending, Mason believes. Ratings agencies did not properly rate securities. Banks encouraged the selling of mortgages by not monitoring the mortgage brokers. Bank regulators and the Securities and Exchange Commission turned the other way for too long, Mason says. Even Congress ignored this growing problem by not addressing the needs of the individual consumers.

Mutual fund investment managers bought the mortgage-backed securities because they provided the high yield that investors wanted - so investors are equally at fault.

"We see a fat yield and we go out and buy it," Mason says. "Shouldn't we know better?"

Of course, private citizens ultimately took out the loans and refinanced when the deals looked sweet.

"It becomes completely circular," Mason says. "We're all complicit."

The first step toward recovery is owning up to our mistakes.

Some banks are starting to disclose their problems: Citigroup will write off $5.9 billion for the third quarter of 2007. UBS will write off $3.4billion.

Around the same time those figures were revealed, however, the US Federal Reserve Board lowered the primary lending rate by 50 basis points. And the European Central Bank pumped $130 billion into banks in an attempt to spur lending to continue there.

Government bailouts will only delay the inevitable, Mason says. Sub-prime mortgages currently amount to about 13% of total mortgage loans outstanding, or about $1.2 trillion. A market slump like during the late 1980's will occur, Mason says, unless lenders can stem the tide of defaulting loans.

Legislative pushes for loan modifications - which are currently being considered - might only push the industry into greater risk.

"Doing so runs a substantial risk of consumers being used to prop up the mortgage industry in the short term by keeping financially-strapped consumers in homes they cannot hope to afford," he wrote in an October report.

"With no regulatory authority to oversee modification and reaging policies and little transparency with respect to those arrangements," Mason concludes, "there is a distinct possibility that extensive modification will hurt consumers and investors alike. Again."

***

He doesn't want to see history repeated. He wants everyone involved to realize what happened, and he wants everyone to learn from this crisis and move forward.

Until they do, Mason will continue his research.

And you'll probably see him on TV or read his name in the papers.