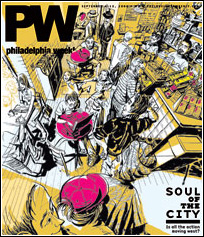

Deep Question

Will dredging the Delaware mean more jobs for our longshoremen?

From the June 11, 2008 Philadelphia Weekly.

There was a time when every longshoreman carried a knife, and many packed pistols.

They hauled bundles of bananas on their shoulders and lugged 200-pound burlap sacks of cocoa beans in the dark hulls of dank, foul-smelling ships. And they did so whether it was 100 degrees under the blazing sun or freezing cold with blowing snow.

There was a time when the row homes in the river wards were populated by broad-shouldered, sinewy-armed men who earned their keep by humping heavy bags from ships to shore along the Delaware River, bringing in the products that fed, clothed and sheltered people every day.

The fraternity of rough-and- tumble longshoremen largely toiled - and continues to toil - anonymously. Who thinks about how their fruit travels to the grocery store from Chile and how lumber arrives at Home Depot?

At the union's peak 50 years ago, there were more than 6,000 laborers in the local International Longshoreman's Association (ILA).

Now they're down to around 700 members who jockey for jobs unloading every boat as though it might be the last ship to ever make call in Philadelphia.

But things might improve once the Delaware River gets dredged 5 feet deeper, a joint project of the commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that's expected to be formalized this month.

"The reality is that without the deepening project, we wouldn't have a future," says Marty Mascuilli, secretary treasurer of ILA Local 1291.

***

Nathaniel Davis, 61, arrives at the longshoremen's hiring center at Front Street and Packer Avenue every morning, seven days a week, at 5:30.

"You got to come down here every day," says the 35-year longshoreman. "If you don't come down here, you don't have a job."

This is where assignments are doled out on an as-needed basis - generally by seniority - depending on the number of ships expected at the terminals.

On this day Davis sits in his white Buick LeSabre listening to samba, waiting for word on a ship rumored to be arriving in the evening. The Virgin Islands native who now lives in West Oak Lane raised five children on his longshoreman's wages, but the inconsistency of the job cost him his marriage.

"This is a man's place," he says. "It's not an easy job."

If they're lucky, longshoremen find work four days a week, with shifts running around the clock. Some days they find themselves heaving bags of beans or hoisting 6-ton rolls of paper at midnight. The only day the port shuts down is Christmas.

"Bills got to be paid," says Curtis Griffin, a divorced 19-year longshoreman whose last three girlfriends broke up with him because he spent too much time on the river.

Most longshoremen stow food in their cars, along with a few changes of clothing, toothbrushes and toothpaste, washrags and enough liquids to last days. Legendary longshoremen have put in as many as 130 hours in a week, and some have dropped dead on the job. A longshoreman lost both his legs this morning when he was struck by a forklift.

Griffin ended a shift at 2 o'clock this morning, started another at 7 a.m., and has arrived at the hiring center around noon to find out about work in the evening.

"How do I know there's another ship tomorrow?" asks William Jones, another longshoreman seeking a multi-shift day. "I got to get the work now."

But shortly after noon a longshoreman walks out of the hiring center and signals to the others that the ship isn't arriving today.

"Today the ship didn't show up," Nathaniel Davis says. "Tomorrow I'll start all over again."

He hopes dredging the river from 40 to 45 feet deep will draw more ships - and more work.

"The workers are here but the river isn't deep enough," he says.

***

"Five feet won't actually solve the problems," says David Masur, director of eco-friendly group PennEnvironment. "You're going to spend hundreds of millions and be stuck with the same problems you have now."

Dredging opponents believe the $305 million project will leave the river 5-feet shy of the depth needed to allow mega-container ships, which would have the most impact.

On top of that, Masur thinks dredging a river that was once a major industrial thoroughfare is dangerous to everything living nearby.

"By dredging a river bottom laced with different toxic pollutants," he says, "it's detrimental to the immediate environment and downriver areas that use the Delaware for drinking water supplies."

He considers it a pork barrel project that'll bring a minimal increase in port traffic.

***

Automation and the containerization of products changed the role of longshoremen over the last half-century, and the shipping industry has steadily become more and more efficient.

But the Delaware River hasn't been deepened since 1942.

Mascuilli, the union leader, says this project will create thousands of jobs on the river, which he likens to an airport.

"Without expanding and widening their landing strips, an airport can't get modern planes," he says. "It becomes obsolete. We don't want to become obsolete."