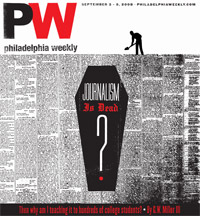

Stop the Presses

A Temple professor tells college kids there's no more inspiring time to be a journalist.

From the September 3, 2008 Philadelphia Weekly.

Chris Stover hushes the crew of 20 students - the section editors of the Temple News, the Temple University student newspaper - and begins the staff meeting.

"This week has been crazy," he tells them. "In the coming weeks, it will not be like this."

A few students laugh. They know it's always a little crazy here in the newspaper office on the North Philly campus.

The newsroom is full of unadorned workstations, but is constantly alive with caffeine-fueled students laughing, yelling, arguing, gossiping, flirting, bitching, writing stories, editing images, laying out pages and doing whatever's necessary to get the next issue out the door.

This is the first production day of the fall semester, the day before the welcome-back issue hits campus, so things are especially chaotic. The staff has been crunching copy and frantically flipping through The Associated Press Stylebook all day. Many were in and out of the office last week too, while other Temple kids were enjoying the waning days of their summer vacation.

"Post your office hours somewhere so we'll know when you'll be here," says Stover, the Temple News editor-in-chief. "You're supposed to be here 10 hours per week."

The staff erupts in snorts and giggles.

"You'll be getting paid for 10 hours," interjects Shannon McDonald, the school paper's managing editor. "I'm not going to lie; you'll probably be here a lot more than that."

Listening in, I feel both proud and uneasy. As a working journalist and a Temple journalism professor, the passion and dedication of the students is the embodiment of what I preach in the classroom.

I've taught various journalism classes to nearly a thousand college students over at least five years, including seven of the staffers in this room. I've worked with these students directly - teaching journalistic conventions, editing their work and encouraging them to develop a voice and style.

I've also gotten to know them beyond the classroom. I've learned things about their family backgrounds, their love lives and their dreams. I know who wants to be the famous network anchor, who wants to expose political injustice and who's looking for a way to combine his musical talents with his passion for words.

I feel a connection to my students, a sense of responsibility, an investment in their future.

And that's where things get tricky.

I've been encouraging college students - including the kids in this very room - to pursue an industry in the throes of a very public meltdown.

***

As has been widely reported the editorial staffs at the Inquirer and Daily News have been decimated over the last several years, with hundreds of reporters, photographers and editors gone, leaving behind vast newsrooms filled with empty cubicles.

Suburban newspapers have cut numerous staffers this year as well, as did the Metro, the free commuter daily.

More than 6,300 people have lost jobs at the top 100 newspapers across the country this year, according to Mark Potts, formerly one of the top editors at philly.com and the author of the blog Recovering Journalist.

Magazine editors of major established titles watch fearfully as advertising dollars disappear. Television stations are losing jobs too: CBS3 and FOX29 both cut staff in a round of budget crunching earlier this year.

Ratings are off for network news, never to return, now that the Internet and cable provides so many ways to learn what's happening.

On top of all the bad business news, there's the ever-growing perception that journalists are biased: The New York Times is liberal, FOX is right-wing and most bloggers are openly partisan one way or another.

Desperate for ratings or single-copy sales, many once well-regarded journalistic outlets have resorted to running regular stories about Britney and Lindsay and Paris and other C-list celebs with glaring emotional issues.

When you're a journalist, telling people what you do these days can evoke a mix of sympathy and disdain.

All of which brings about the ultimate question, the one I've been asked numerous times since I started teaching journalism to college students: How in good conscience can I stand in front of a classroom and encourage college kids to enter a dying profession?

My answer: Journalism isn't dying. It's just evolving.

The public may have turned against traditional media but it doesn't mean they don't want news and information. The challenge now is to figure out how to earn the money to generate the information, and discover the most efficient ways to deliver it.

It's a new media world and, I would argue, the most inspiring time in history to be an aspiring journalist.

***

"You can't put your head in the sand and act like the layoffs and things aren't happening," says John DiCarlo, who's currently serving his seventh year as advisor to the Temple News. "We don't shy from the subject."

Recently several young established journalists from local newspapers and websites - all former Temple News staffers - came to speak to the school's current editorial staff about the business. Finding a job after graduation was a persistent topic.

It's not easy finding work, they each admitted. But if you're committed and aggressive, and if you bring multiple skills to the table, the work is out there.

Of course, these are people who already have jobs.

"The bottom line: If you have a passion for this, don't get scared off," says DiCarlo. "The skills you learn here are going to pay off no matter what you wind up doing, even if you don't go into journalism."

Learning how to interview teaches you how to communicate with people, says DiCarlo. You also learn to deal with deadlines, and all jobs have deadlines. Writing skills are useful across the board.

"I tell students that journalism teaches you how to get involved," he says.

DiCarlo, who covered sports for a South Jersey daily for four years after graduating from Temple in 1998, says that interest in the campus newspaper has remained steady despite the dismal industry news.

"It's not like these kids have to be here," he says. "They're essentially doing full-time work and they don't get paid much."

Editors earn between $5 and $10 per hour, and writers get $15 per story. It's hardly a financial incentive to spend one's glorious college years slaving under fluorescent lights.

But many kids do.

"My father says, 'I hope you find a husband who can support you,'" says Carlene Majorino, a section editor at the newspaper. "But I like journalism so much I'm willing to do it until someone tells me I can't."

***

"It's got to be one of the most exciting times to be in this business," Daily News Editor Michael Days told me in January when I was working on a story about the possible sale of the Metro. "There is so much happening in print and online."

Days, my former boss at the Daily News where I worked for 11 years, may have been putting a smiley face on a grim situation. The DN's circulation has dipped to 110,000 copies a day, fewer papers than the Metro distributes. The Inquirer, which once boasted a circulation of more than 500,000 copies a day, now moves around 334,000 papers daily.

Philadelphia Media Holdings, owner of the Inquirer and Daily News, informed staffers two weeks ago that more job cuts are coming.

The times might be exciting, as Days says, but good luck finding a job.

So the right attitude is: The hell with traditional media. Who wants a job you might lose anyway because a bunch of moneyed suits are unwilling to take a smaller return on their investment?

The future of journalism isn't working for the Man, I tell my students. It's being the Man.

***

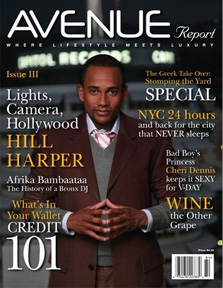

"People told me I was crazy," says Toyin Awesu, publisher of Avenue Report, a glossy magazine that targets successful African-American men. "People still tell me I'm crazy."

By the time Awesu graduated from Temple in May 2007, she'd already published her first issue featuring the smooth rapping, genre-blending Lupe Fiasco on the cover.

Just 23, Awesu has published four issues of Avenue Report with a circulation of some 9,000 copies in specific areas. Next year the magazine will be available in Borders stores and Barnes & Nobles around the country.

And this is Awesu's first full-time position in journalism.

"Ideally, I wanted to work for a magazine first," she says. But she jumped in headfirst when she was able to secure financial backing for her dream. She now oversees every aspect of the operation, including a small staff.

"It's been very hard," she says. "As much as I love writing and editing, this is a business. It's very costly up front and you may not make any money until year four or later."

Small-circulation magazines can cost tens of thousands for printing alone, but there are ways to become your own media outlet that don't cost anything.

David Hobby was a veteran photojournalist for the The Baltimore Sun in 2006 when he started compiling information about photo lighting on a blog called Strobist. He launched with zero overhead, using free web space from blogger.com and connecting to free WiFi at the public library.

The site, which offers lighting tips, inspirational images and news on the latest gadgets, quickly developed a loyal following. Hobby now gets about 1.5 million page hits a month and recently topped 2.5 million in unique visitors.

"I've really been instrumental in teaching 2 million photographers how to use light," he boasts.

The site features a full roster of advertisers and a waiting list of companies wanting to hawk their wares and services. Revenue is so strong that Hobby, a father of two young children, quit his newspaper job last month to run the blog full-time.

"I couldn't afford to go back to the Sun, financially speaking," he says with a chuckle.

Hobby believes ventures like his - small content generators, aggregators, repurposers and other niche media - are the future.

"The old Fourth Estate is disintegrating," Hobby tells me. "Rather than rely upon these big towers of journalistic integrity, like The New York Times or TV network news, the aggregate of all the smaller operations is going to be bigger than traditional media."

Denise Clay, past president of the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists and a current Temple adjunct, says, "If you don't grab the bull by the horns real quick, you'll find yourself in a job asking, 'You want fries with that?'"

Journalism will always exist, says Clay. It's just going to look a lot different.

"This generation gets information in ways we can't fathom," says Mark Potts, formerly one of the top editors at philly.com. "You just have to broaden your definition of what a journalism job is."

***

But for every modestly successful independent blog or website, scores of journalistic experiments come up short, like RealPhilly magazine and Inquirer News Tonight, just to name two.

After former Inquirer reporter Eils Lotozo was laid off in 2007, she tried to establish a home and design feature story/photo service for newspapers. On her website, she posted stories every week and made them available for purchase with rates determined by circulation. She developed the concept from scratch, believing that newspapers with shrinking staffs would be in need of content.

It never caught on.

"When my venture didn't pan out," Lotozo says, "I had to reconsider my life in journalism after more than 20 years in the field and what had been a pretty wonderful career."

There weren't any jobs and being a freelancer was financially unreliable. Last month, with a family to support, she took a communications job at Haverford College.

"There are some fine aspects to this evolving journalism world," Lotozo says. "But I still fear for the world and democracy. Who will pay for the time it can take an experienced journalist to follow the key people around, go to the places, make the phone calls, do the research, reflect?"

***

The generation of kids I teach at Temple today needs to understand the business of journalism and how to fund their media endeavors.

The local anarchist newspaper, The Defenestrator, raises cash with concerts; two.one.five magazine has subscriber-only parties (where you either drop the annual subscription rate at the door or go home); South Philly-based music mag Wonka Vision sells tracks on promo CDs that then get distributed with the magazine.

Nearly every staff-produced image you see on the South Jersey Courier-Post website is available for sale. Though hardly a novel concept, the Courier-Post has taken the notion one step further.

Photojournalists are instructed to submit dozens of pictures from events, rather than one or two images that are typically used to illustrate a story. Photographers upload images to the Courier-Post website, creating galleries of images that inform and entertain as well as possibly earn additional income for the paper. Events with the greatest sales potential, like high school proms and graduations, are big.

"I think we shot every high school graduation in South Jersey," says Avi Steinhardt, the newspaper's assistant director of photography. "We did seven in one night. It was a little insane."

Shooters documented hundreds of students receiving their diplomas and placed the images online where they were available for $15 a pop for a 5x7 and $25 for an 8x10.

"It's not as lucrative as advertising, but it brings in revenue," Steinhardt says.

It's not photojournalism either. But at least the shooters get to keep their jobs - as opposed to the Inquirer and Daily News, where the photo staffs have been merged and reductions are imminent.

***

"Would I spend $50,000 for my kids to study journalism?" ponders Dan Rubin, an Inquirer columnist, Penn journalism professor and father of two college-age sons. "They better love it."

Rubin fell in love with journalism during the Watergate, journalist-as-superhero era and pursued the craft so he could be a student of the world.

"A notebook," he says, "could get me into anything."

He encourages his students to appreciate journalism for the same reasons.

"Journalism may not be their entire careers," he tells me, "but it's a great way to see the world at its extremes."

On this we agree. Because of journalism I've experienced lots of things most people only read about.

I got to play basketball with former 76er Jerry Stackhouse and his brothers at his family's home in Kinston, N.C. I drove a racecar 170 miles per hour around Pocono Raceway. And I met all-time Japanese home-run king Sadaharu Oh.

No, it's not all hearts and flowers. One Sunday morning in 2005 I interviewed a 13-year-old boy hours after he witnessed his mother stabbing herself to death in their South Philly home. She'd killed her two other young children, a 10-year-old boy and 6-year-old girl, moments before taking her own life.

It was the most heartbreaking conversation I've ever had.

The next day I sat in a North Philly rowhome and listened to a wailing mother whose 9-year-old son was shot to death on 16th Street, only three blocks from my current office at Temple. I can still hear her painful, high-pitched sobs.

Being a journalist has taught me to appreciate every moment of every day in a way that lawyers, financial analysts and advertising executives never will.

***

If you're lucky enough to find work in journalism, there's no guarantee the public will appreciate your efforts.

My girlfriend, a television reporter for many years, was often told she blinked too much while on air. Rather than listen to what she was saying, viewers focused on the superficial.

As a reporter I was yelled at by cops who didn't like stories I wrote. I was detained for obstruction of justice by federal agents for "interrupting" a drug sting in Ft. Lauderdale while just trying to do my job. A priest once snapped at me when I asked for information about a young murder victim.

Mayor Street chastised me in the middle of a press conference while I was shooting pictures of him for the Daily News. "You're trying to get as many crazy shots as you can," he barked.

Curt Schilling yapped at me in spring training, locals threw rocks at me and other journalists in Juniata when we covered a murder/ suicide. Former Eagle Duce Staley cursed and called me Bruce Lee (my mother is Asian) when I took his picture in the Vet locker room after he was injured. When I wrote about what happened with Staley, I was barraged with angry emails. "It's assholes like you that give credence to the old saying my father taught me, 'You can't shine shit,'" read one.

Some of my harshest critics have been those within the industry.

A few years ago a friend connected me to Arthur Frommer, the man behind the Frommer's travel guides and other travel magazines. I submitted a story to him about the wineries of the Le Marche region of Italy.

"One does not make a magazine article simply out of a chronological record of your visits to various wineries, especially a visit that result in a giant zero, as the above visit did," he wrote in an email. "The language above is totally vacuous. A writer makes choices about what he writes; he works to support an eventual theme, an overarching point to be made."

It got worse:

"There is no such point in this article, no shaping of the material, no discriminating selection of interesting events or statements, simply a quiet recitation of several fairly innocuous visits to a number of wineries," he continued. "There is nothing here."

Again, there's the question again: Why would I encourage young college students to follow this path?

***

"I could be out enjoying my senior year but I choose to be here," Temple News' Chris Stover tells me.

Stover - who was also the editor of his high school newspaper - is a broadcast journalism major. He thinks combining the skills and knowledge of the different genres will make him more marketable.

"May 14th is graduation, which is scary," he says. "Before graduation I'd like to have something lined up. I don't care if it's in Erie, Pennsylvania, Juneau, Alaska, or Lubbock, Texas."

Someone taught this kid well. I wish I could take credit, but he's never been in one of my classes.

***

I'm not rich and I'm not famous.

But I haven't regretted choosing journalism.

I've been able to write a story about the Philadelphia legal team fighting the U.S. government for unjustly abusing innocent Iraqi citizens at Abu Ghraib. I profiled West Philadelphia High School Auto Academy's eco-friendly car builders who won an international competition. I've written about dozens of victims of pointless crime in this city, trying to attach faces to grim statistics.

I don't think I've made a great difference with my journalistic work during my 15 years in the business. But I hope I've taught people a little more about their world.

I apply the same philosophy to teaching.

The future of journalism is uncertain. The students of today - more so than ever before - have the ability to shape what the profession will someday look like.

It's my job to make sure they know that.