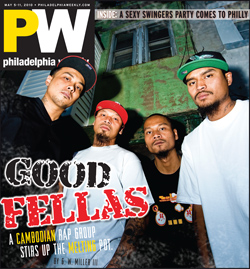

Good Fellas.

Cambodian rappers AZI Fellas drop a positive beat on their troubled past.

From the May 5, 2010 Philadelphia Weekly.

It's a Monday evening in April and the back door leading to the alley opens and closes steadily as people stroll in and out. Cigarette smoke from outside wafts into the room, a dimly-lit rowhouse basement in Olney with walls painted black and strips of sound-proofing cushions attached to the ceiling in random spots.

Sokorn Touch, known as Korn Swagger, sits at his computer in front of his homemade recording booth, listening to beats, his head gently bobbing along. Next to Korn, Joe In - clad in a flat-brimmed Phillies cap turned slightly askew - rocks his head from side to side with the beat - an electronic rhythm with a meandering Asian lilt floating over the bass line.

"We always want to add a little flavor to it," says In of the lilt - a nod to Korn's and In's Cambodian heritage.

The two make up half the Philly hip hop group AZI Fellas, an Asian-style Wu-Tang Clan creating conscientious music based upon the craziness of their lives. Rooted in their urban experiences as well as their dramatic family histories, the AZI Fellas spit lyrics that speak of a common disenfranchisement, backed by a beat that makes you want to bounce.

Korn, 30, clicks his keyboard a few times and a high-pitched female singer's voice screeches over the beat in Khmer, the official language of Cambodia.

"It's an old, traditional song," offers Korn, referring to the lyrics. "You play this somewhere and all the old Cambodian people will start singing too."

Korn and In, 30, continue swaying to the pulsating beat as Raymond Ros, another member of the group, joins them after walking through the alley door.

"Man, this is some real in-your-face Cambodian shit," says Ros, 25, known as Razor Sharp. "We usually try to blend everything."

Their music generally incorporates tinny Cambodian tunes with heavy drums, East Coast-style attitude and powerful lyrics - about their families fleeing the genocide of 1970s Cambodia, living in refugee camps, arriving in Philadelphia with nothing, growing up as outsiders, living on welfare, joining gangs, selling drugs, watching friends get killed, hustling to survive and raising their families.

"Hip hop has always related to poor people in the struggle," says In, who performs as Joe Hanzsum.

"It relates to people's problems," adds Korn.

"That's why we relate to it," In says. "We got a right to say what we say."

By now, the narrow room packed with musical instruments and sound equipment swarms with activity. Five more people have entered through the alley door, including a few teenagers and two African-American rappers who are all part of the AZI family.

Korn's mom takes it all in while observing from halfway up the basement steps.

"When you buy me big house?" she asks with a laugh.

***

In a genre that reveres authenticity, it's hard to argue that anyone could be more street than these guys - even though they're Asian. And in a city that has unsuccessfully been dealing with tensions between Asian and African-American students in the public schools and elsewhere, the AZI Fellas may be the perfect bridge between the two cultures.

"When you listen to our music, you don't hear race," says In.

"Yeah," says Korn. "We don't get people saying, 'Damn, those are some hot Asians.'"

"Most people think we're black when they hear us anyway," In says with a chuckle.

They want to use their music to bring people together, to pull themselves out of their personal situations and to help their families. Their ultimate goal is to take their music international so they can help rebuild Cambodia, a nation still scarred by decades of war and political turmoil.

On Friday, May 7, the AZI Fellas will perform at the Asian Arts Initiative (1219 Vine Street) in a benefit for Tiny Toones Cambodia, an organization that helps at-risk Cambodian youth through breakdancing, hip hop music and art.

The question remains whether four humble yet provocative Cambodian guys with sketchy pasts and no desire to be commercially appealing can make it out of the basement in an industry that rewards image.

"Asian or not, if you plan to make music your job, you definitely have your work cut out for you," says Scott Jung, better known as CHOPS, a hip hop producer who was a member of the pioneering, Philly-based, Asian-American rap group Mountain Brothers. "When you're talking about making rap music, you have to be 100 percent with it. You have to earn your spot."

***

On the eve of the Cambodian New Year's festival in mid-April, the AZI Fellas are back in the basement, as they are nearly every night.

The fourth member of the group, Korn's brother Sokhon Touch - known simply as Touch, bangs the drums while Korn plays guitar for a five-piece pick-up band they've assembled for a spot gig at a one-year-old's birthday party. They rehearse a few catchy Cambodian classics - it will be a family crowd - but neither Korn nor Touch seems inspired by the kitschy, 80's-sounding Asian pop.

"I'm trying to get the right beat," Touch says excitedly, a Cambodian flag draped on the wall behind him. "I just can't get it. I'm about to hit a hip hop beat."

After an hour of rehearsal, he wants to unleash.

Joe In sits on a nearby couch, listening to an iPod. He scribbles lyrics in a spiral notepad between munching Doritos and mouthing rhymes to himself.

When the pick-up band practices their final number, Touch finally drops a hard-pounding beat just for fun. In jumps up and starts shaking his hips.

"This could be a hip hop song," In says over the cacophony.

After practice, Touch meekly says, "The birthday gig is just for money."

"But AZI is for real," In follows.

When the birthday band exits out the alley door, Korn takes his seat at his computer and In begins spitting in the booth.

Upstairs in the kitchen, Korn's mom cracks pepper using an old-fashioned wooden pestle and bowl, preparing spicy pickled cabbage dishes to sell at the Cambodian New Year's celebration the next day. The pounding echoes into the basement with a hard, steady rhythm.

"She's got the beat," Korn says.

***

The four members of the group grew up together in Olney, rapping in ciphers on street corners and beat-boxing by the playground.

"Rap is what we grew up on," Korn says. "We were just trying to duplicate what we liked."

But music surrounded them. Korn's father loved the blues - especially Muddy Waters - even though he couldn't understand English. Korn and Touch taught themselves how to play various instruments - from the trombone and drums, to the keyboard and guitar. They also listened to Cream and Led Zeppelin and Soundgarden, as well as the Cambodian songs they heard on DVDs, VHS tapes and at festivals.

By the late 1990s, the quartet began building the studio in the basement. They played traditional Cambodian music at weddings and parties to pay their bills. They worked with other artists to develop beats and produce music, with Korn honing his self-taught mixing skills along the way.

In 2005, the AZI Fellas decided to officially pursue their dreams. They first performed at the Hot Import Nights auto show at the Convention Center, and then played various venues around the city - the Khyber, Trocadero, Egypt, Transit and Tipsy, a popular Asian hotspot owned by friends on Frankford Avenue.

They've performed live about 50 times and they independently produced, promoted and sold two albums. Their third is set to drop this summer.

In addition, they have a stable of artists working under their label All Corners Covered - the name of the barbershop near Wyoming and D streets where In gets his hair cut. In's barber, Joseph Frazier - known as Jodie Onez, performs with the group DNOC on the AZI label.

"It's no run of the mill shit," Frazier says of the AZI Fellas' sound. "Their music is the product of their country. They merging cultures and shit."

***

The AZI Fellas rap about their current situations but they focus on how they arrived at this point.

"We want to help people, educate them through our music," says Joe In.

Until the 15th century, Cambodia was home to the world's largest pre-industrial civilization, Angkor. At it's peak, more than one million people lived amongst Angkor's ornate sandstone temples. The ruling monarchy then battled with other powers in Southeast Asia for the next three centuries, leaving the people in limbo. The French colonized Cambodia in 1863, eventually making it part of Indochina.

In 1953, Cambodia was granted independence and the monarchy again took control. As the war in Vietnam escalated in the 1960s, Cambodia remained neutral.

Then the war came to Cambodia.

Both sides of the conflict invaded Cambodia in 1970 and the reigning prince was ousted in a military coup. Civil war broke out in the small country, with the communist Khmer Rouge army - supported by the communist North Vietnamese - pitted against the United States-supported Khmer nationalists.

The communists won.

In 1975, Pol Pot became the state leader. For the next three years, he tried to return Cambodia to the pre-industrial age, expelling people from cities and forcing them into labor camps.

"Pol Pot believed Cambodia could only function as an agrarian society," says Ben Kiernan, the founder of the Cambodian Genocide Program at Yale University and author of numerous books on Cambodia. "He believed that cities were parasitic and polluted with foreign ideology."

More than 1.7 million people - around 21 percent of the population, were starved to death or murdered, with many dumped into mass graves dubbed the Killing Fields.

Many Cambodians escaped to refugee camps in Thailand. Upwards of 500,000 people were detained in guarded, open-air camps where they had to fashion shelter out of bamboo and palm leaves. Some lived in the camps for more than a decade despite Pol Pot's reign ending in 1979.

"Every single person in Cambodia was touched by the tragedies," says In.

His mother was pregnant when she was chased into the jungle by the Khmer Rouge army, he says. He was born inside a Thai refugee camp, just like Korn and Touch. In's father was forced into service with the Khmer Rouge army. He never saw him again and presumes he died in war. When he was 2-years-old, In and the remainder of his family were sponsored to emigrate to America.

"If you got out, you was blessed," In says.

***

"Whenever there is a crisis in another country, my district is going to get a bunch of new people," says state representative Mark Cohen, who has represented parts of Olney for 36 years. "It's always been in a constant state of change."

Cohen grew up near Broad and Olney and attended Central High. His neighbors were from Switzerland, the Ukraine, Russia and Italy. Now, his district features dozens of native languages with people from throughout Asia, Central America and Africa.

Around 2,000 Cambodian families arrived in Philadelphia starting in 1979, continuing through the early 1990s. An estimated 14,000 refugees landed here thanks to the church and synagogue groups who sponsored them.

Most began their American existences in South Philadelphia before more permanent housing was found for them, often in Cohen's district. There are about 20 Cambodian families within a block of Korn's house.

"The majority of us were poor and had no formal education whatsoever," says Rorng Sorn, the executive director of the Cambodian Association of Greater Philadelphia. "Then they put us in areas already in poor condition."

Sorn, who spent 8 years living in refugee camps in Thailand with her parents and six siblings, was initially placed in a third floor efficiency apartment with 12 relatives. The family took turns sleeping on the floor.

"My mom was crying all the time," she remembers. "She felt homesick even though she didn't have a home in Cambodia anymore."

The refugees, most of whom had been living in shanty towns at the foot of the mountains, received no orientation to this foreign place, not even English language training.

"They just told us, 'Kids go to school. Parents go to work,'" says Sorn, who was 19 when she landed in Philadelphia.

She petitioned to attend South Philadelphia High School and graduated after two years. Then she attended the Community College of Philadelphia. After classes, she caught a van to a meat processing plant in New Jersey where she, her parents and her older sister peeled chicken off the bone from 4 pm until 2 am every day. In the summer, she spent her days picking blueberries and other produce, usually beginning at 4 am.

The parents of the AZI Fellas have similar stories.

"Cambodians worked hard, striving to become good citizens," Sorn says.

Between working so much and not being able to navigate the city because of poor language skills, many adults weren't able to help their children adjust to life in Philadelphia.

Left to fend for themselves, many teenage Cambodians joined gangs.

***

On welfare and barely able to speak English, the young Cambodian refugees were easy targets when they first attended public schools in Philly. They were picked on and called names, and sometimes they got roughed up on the streets of their predominantly black neighborhoods - the exact same situation that continues to plague Asian immigrants today.

"Back then, there were no guns but there was a lot of fighting," says Touch, who was kicked out of Bodine High School because he scrapped so much. He later earned his GED.

Gangs started as a form of protection, then evolved into turf battles. The AZI Fellas, living east of 5th Street, aligned themselves with the Bloods while Crips ruled west of 5th. When the gangs started dealing drugs in the mid-1990s, the violence erupted.

"You could hear gunshots every night back then," says In.

One night after Korn and a few friends drove home from the movies, another car followed them. When Korn's crew parked and started walking toward his house, the passengers in the second car released a barrage of bullets.

"They were looking for other Cambodian guys," Korn claims. "It was mistaken identity."

No one was injured.

While most of the Asian gang violence in Olney and Logan has slowed down since the 1990s, tempers still flare. Raymond Ros spent 8 months in jail recently after being connected to a shooting on Delaware Avenue. He was released when the true shooter was identified.

In's brother is currently in jail, convicted of third-degree murder. His other brother is in jail for robbery. In served three months in prison after being busted for selling drugs.

"It was just stupidity," says In of his gang days.

None of the group members shy away from their troubled pasts.

"If your life was really good, you wouldn't be a rapper," says Touch, who spent two months in the brig and was dishonorably discharged from the military after going AWOL from his Navy base in Washington so he could attend a Sixers' game during the NBA Finals in 2001. "If you were born with a silver spoon, you wouldn't have nothing to rap about."

***

The next day at the Cambodian New Year's celebration near 58th and Lindbergh in Southwest Philly, Joe In and his 7-year old daughter linger by the food stalls when he sees the crowd of people open up.

"That shit's about to go down," he says before pulling his daughter away from the mob.

In the ensuing bedlam, four people are stabbed right in front of the booth where Korn's mother sells her spicy pickled cabbage.

"It's just stupid old gang shit," In says later. "It's real corny. We outgrew that stuff a long time ago."

He gave up the illegal hustle when his mother passed away from a brain aneurysm in 2003. Now, In, a father of two, works as a self-employed contractor when he's not rhyming in Korn's basement.

"They turn their difficult backgrounds into positives," says Sorn of the Cambodian Association.

The AZI Fellas performed at the Association's 30th anniversary celebration last December.

"It's inspirational and empowering how they tell their life stories," Sorn says. "They are a link for us between Asian culture and American culture."

***

The tight knit Cambodian community in Philadelphia has embraced the AZI Fellas but it will be difficult for the group to make it out of Korn's basement.

"We want to be successful at what we do," Korn states of their intensely honest lyrics. "We don't conform to popular music."

The problem is that the industry promotes bling and the stereotypical gangster lifestyle, according to Michael Coard, a Philadelphia attorney who also teaches Hip Hop: a Race, Gender and Class Perspective at Temple University.

"The bastards controlling the production of hip hop don't push music because it's good," says Coard. "They push the lowest common denominator, whatever they think is going to sell."

When Mountain Brothers, one of the first Asian-American hip hop acts to sign with a major label, sent demos out in the early-1990s, they sent them two ways: one with their picture attached and one without.

"The ones with no picture got us calls back," says former Mountain Brother, CHOPS. "We were judged on our music and not by the color of our skin."

Since Mountain Brothers broke up in 2003, CHOPS has performed with or produced beats for Bun B, Lil Wayne, Jeezy, Chamillionaire, Paul Wall, The Game, Raekwon, Fabolous, Talib Kweli and Kanye West, among others.

He's very aware of his image, preferring not to discuss his specific age, hometown and other vital information for fear that it might harm his reputation.

He's adapted with the industry over the years. When he began in hip hop, he was all about the message, the lyrics. Now, he primarily works behind the scenes making beats.

"As time goes on, you have to make money doing what you do," he says. "If I kept doing what I was doing ten years ago, I wouldn't be in business anymore."

***

A week after the Cambodian New Year's festivities, Korn sits at his computer in the basement. He announces that he was fired from his job as a cable technician after ten years with the company. He blew off work too much to tend to his music.

"I'm going to do this full-time for a while and see what happens," he says with a wry smile.

A hollow club beat emanates from the speakers

AZI artists Khalid Hall - known as Kalek, Ranz Lee and Willie Green enter through the alley door and approach the recording booth.

Hearing the beat, Green starts rocking back and forth and then drops lyrics about his life.

"We in the gutter with the mayor Michael Nutter," he rhymes.

When Green finishes, Joe In says, "That's so smooth."

The five discuss the beat for a few moments - seriously at first and then joking around with each other.

"We're pretty open to everybody," Korn says of the artists the AZI Fellas work with, most of whom are African-American. "We're in the same boat as them."

All have day jobs, and most have side gigs in addition. They hustle and struggle to support their families, and they share a common passion.

"Music is music," Korn states. "You don't have to be a certain age or certain color for it to be good. If it speaks to you, it's good."

* The version that ran in the Philadelphia Weekly was edited.