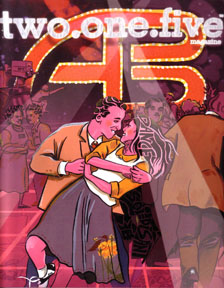

Dancing in the Dark.

Bandstand brought rock n' roll to America. But where did all the black folks go?

Published in the Winter 2008 issue of two.one.five magazine.

Jackie Massey saunters to the deejay table and snaps, "We need some James Brown! We need to get these people dancing!"

The small crowd of predominantly African-American teachers and staff from West Philadelphia High School mill about in their suits and Sunday best, some browsing the buffet table with Sterno-warmed turkey, stuffing and ham. Others at the annual holiday party quietly sit at the large round tables set up around the empty dance floor in Studio B of The Enterprise Center, formerly known as the home of American Bandstand.

The deejay smiles but responds, "It's too early."

Massey, sporting a red blazer and a crown of faux poinsettias, slinks away as the Jackson 5 belt out a jaunty Christmas tune. She retreats to a table where the vivacious technology instructor launches into laughter with co-workers. She's mid-conversation when Clara McCann approaches and touches her shoulder.

"I want to show you something," McCann says.

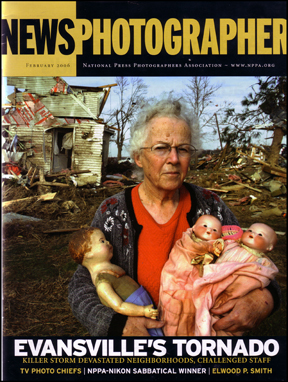

She escorts Massey to a large photograph on the wall, a black and white snapshot of a young Dick Clark surrounded by a sea of white faces on the set of American Bandstand. Two young African-American girls sit inconspicuously in the background, off to the right.

"That's what I looked like when I was a little girl!" McCann squeals as she points to a partially obscured, dark-skinned face.

"It must have been later in the show," Massey says wryly, "because they didn't permit us on Bandstand in the beginning."

Every day during middle school, Massey recalls, she and her friends ran home to watch American Bandstand, one of the most popular television shows in the country in the late 1950's. In her West Philly home, the girls emulated the dance steps and memorized the names of all the regular dancers.

Massey dreamt of going on the show but she never tried to get in.

"We were not permitted," she states with pointed diction.

***

For Baby Boomers across the country, those two simple words - American Bandstand - evoke a wave of nostalgia, especially when they remember the Philadelphia era from 1957 to 1964. Those were innocent times with bubble gum music, bouffant hairdos and boys in jackets and ties. The doo-wop songs from that era spoke of unrequited love, and the dances featured hand-holding and eye contact.

It was all so sweet.

Of course, America was a different place fifty years ago. Segregation was blatant in some places and subtle in others. Rock and roll music was in its infancy and considered by many to be the product of the devil. Television was novel. And quaint Philadelphia was a thriving manufacturing hub populated by working class stiffs from all sorts of racial, ethnic and social backgrounds.

American Bandstand, which broadcast live from WFIL's studio here at 46th and Market Streets, championed the cause of rock and roll by disseminating a clean-cut, watered-down version of youth culture to more than 5 million households, five days per week. During special events, more than 12 million people tuned in.

"What Bandstand sent out was an illusion, a romance," says Charles Amman, author of the soon-to-be-released Bandstand book, "The Princes and Princesses of Dance."

Bandstand wasn't real. It was a fantasy world, a soap opera. The fans were drawn to the regular dancers - ordinary local teens - the way we're now absorbed with Britney, Beyonce and Brangelina. The dancers were characters on a show, and they became household names.

Last August, The Enterprise Center celebrated the 50th anniversary of the first national broadcast by unveiling a huge mural featuring 11 of Bandstand's most popular dancers.

And the errors of the past were suddenly so glaring.

"There are no African-American dancers represented," says Carissa Jones, the special events manager for The Enterprise Center, which, ironically, is an incubator for minority owned businesses. "But if there were African-Americans, it would be a lie. That wasn't part of Bandstand."

***

When the Electric Slide comes on, Jackie Massey corrals a group of West Philadelphia High School women and they line-dance in the center of the orange-colored floor. She counts steps out loud, helping those uncertain about the moves.

On the room all around are reminders of the studio's glorious past - pictures of gangly white teenagers dressed like little adults. They hold each other gingerly, frozen in time with stoic faces and stiff arms.

Aside from the one pair of young African-American girls, there are no other black faces in any of the old photographs.

"We couldn't dance while black," says special education teacher Pat Burch who grew up nearby at 51st and Haverford. "We weren't allowed in but we snuck in the side door. We used to just hang in the back. We didn't dance."

***

On any given day, there would be hundreds of teenagers waiting to get into Bandstand. They arrived from around the region, often cutting school or skipping the last few periods to get in line early.

The lucky 150 or so chosen would dance the Stroll, the Strand, the Cha Cha, the Stomp, the Mashed Potato, the Circle Dance and Jitterbug before a national audience while Dick Clark stood disinterestedly at his podium.

They shuffled their feet, twisted their hips, rolled their heads and twirled each other around and around every weekday from 3:00 to 5:00.

The biggest pop stars of the time - Paul Anka, Chubby Checker, Freddy Cannon, Frankie Avalon, Little Richard, Connie Francis, Fabian, Bobby Rydell - would lip-synch their latest hits live on stage.

Between dancing and performances, Clark spoke to the dancers on air about where they were from and what they were into.

"One time I said I liked stuffed animals," remembers regular Carmen Jimenez. "A week later, 5,000 stuffed animals came in the mail."

It was a national show but it definitely had a Philly feel. You could see the big white collars from the West Catholic girls' uniforms poking out over their sweaters. Pennants representing the region's high schools - Bartram, Olney, Central, Wilmington, Southern, Roxborough, Pitman, Northeast Catholic, Souderton and Girl's High, among others - hung prominently on the walls. And the kids had a swagger, an I'm-cooler-than-you attitude.

The crowd, however, was predominantly white. Some days, it was completely white.

"In all the years I went on Bandstand, I saw maybe two or three black couples," says Eddie Kelly, a Kensington native who danced on the show daily from 1959 through 1961. "I guess they felt uncomfortable, out of place."

***

Bandstand actually began in 1952 as an MTV-like production. Host Bob Horn presented short films called Snader Telescriptions - visual recordings of musicians performing their hits. West Catholic students who were fans of Horn's old radio show filled the audience. While the films were broadcast, the kids jitterbugged in the WFIL studio.

Someone got the idea that the audience might enjoy watching the kids dance.

The retooled show - focusing on the live dancing - became a huge local hit. It was a cheap way of filling the afternoon time slots and soon, every major city copied the Bandstand dance-party format.

In 1956, Horn was busted for drinking and driving, and then allegations popped up about him molesting young girls. The station axed him and eventually replaced him with Dick Clark, an ambitious Syracuse University grad who had been hosting a show on WFIL radio.

Viewership only increased and the line to get in grew and grew under Clark's stewardship. Within a year, WFIL convinced the ABC network to run the program nationally.

Almost overnight, the confluence of new technology, new music, energetic dancers and a charismatic host made Philadelphia the center of the teenage universe.

"When it went national, it went through the roof," says author Charles Amman.

***

Not everyone was pleased.

"There were stations in the Southern part of the country that wouldn't carry the program at first because it was an integrated group of kids dancing," says Lew Klein, Bandstand's executive producer during the Philadelphia years.

The segregated south was a large market to lose but Klein says that the Bandstand crew never established a whites only policy.

"There was no concentrated effort to change anything from the way it was - a mixed audience," he says.

When the huge audiences started watching, the stations down south joined the line-up.

"Bandstand truly helped to get acceptance of integrated, mixed dances," Klein says. "It just created a difference in the attitude of teenagers toward black and white relations."

Critics argue that the majority of minority faces that appeared on the show were the ones playing instruments and singing songs. No matter what the stated rules were, the perception existed that American Bandstand was for white folks only.

"If you was a performer, you got in," says Della Clark, president of The Enterprise Center. "If you wasn't a performer, you didn't get the time of day."

***

Bandstand promoted this new brand of music that evolved from traditionally black genres like blues and boogie-woogie. And the dance moves were slowed-down, tamer versions of what African-Americans had been doing for years - black folks called it the Bop, and their version had less twirling and more freestyling.

Joe Fusco spent afternoons at a candy store on Passyunk Avenue near Christian Street where the owner had a jukebox and the black kids danced. He watched them do the Slop, the Chicken, the Grind and the Strand. He took those moves, modified them, and displayed them on Bandstand.

"We brought the Strand on the show and it was really popular," Fusco laments. "They never got credit for it."

In the 50's, Diane D'Santo went to all the big dance joints - the Milkbar in Yeadon, Wagner's Ballroom, Chez-Vous, the Optimist at Broad and Moore. Her regular spot was Dave's, a candy store with a jukebox at 17th and Tasker. She spent her teen years dancing with mixed crowds, imitating what she thought looked cool.

"Everything on Bandstand came from black culture," D'Santo says.

***

The Bandstand Regulars - like Fusco, Arlene Sullivan, Eddie Kelly, Carmen Jimenez and Justine Carrelli - became national celebrities. They appeared frequently in teen mags, their lives and romances documented for the nation. Fan mail poured in by the thousands, with some Regulars receiving more than 1,500 letters per day. The local post office ran out of mailbags at one point.

"I'll never understand it," says Sullivan, among the most popular Regulars in the show's history. "I wasn't the prettiest girl. I wasn't a fashion plate. I wasn't even that good a dancer!"

Sisters Carmen and Ivette Jimenez received numerous bus tickets in the mail attached to invitations to visit fan's homes. So the sisters went to Michigan and Indiana and they traveled all over Pennsylvania.

"One day on the show, I said I always wanted to milk a cow," Carmen remembers. "Next thing you know, I'm in York, Pennsylvania milking cows with a fan's family."

The sisters stood out on the show because they each had a blond streak bleached into their dark hair. Teenage girls across the country starting streaking their hair after they saw the Jimenez girls on television. The sisters inspired the character in John Water's film, Hairspray.

After Fusco wore an ivory horn on his lapel, his mail tripled.

"They wanted to know where to get it so they could wear one too," he says with a laugh.

One day, one of his pals wore a sweater backwards on the show. The next day, Fusco saw people waiting in line for the show with their v-necks facing the wrong direction.

"We set the trends for everything!" Fusco says. "The whole time, everybody's trying to get on that camera. The more you got seen, the more mail you got."

And the more mail you received, the more Dick Clark would feature you in spotlight dances and interview you during Roll Calls.

Clark, who probably received the least fan mail, controlled the tone of the show. He chose the performers, music, dance contests and even the Regulars. When he saw kids grinding, he'd bark, "You're not going to be in the next spotlight dance if you keep doing that!"

If he saw couples working the cameras too much, he chided them over the loudspeaker, "Kenny and Arlene, step back from the camera."

"We were all hams," says Justine Carrelli, the gorgeous blond who became a national obsession as she danced with her then-boyfriend Bob Clayton. "That's why you were there. You wanted that limelight."

The dapper young couples seemed so romantic.

"They were just floating across the screen," says Amman, the author, "and the nation fell in love."

***

The reception in Philly wasn't always so warm.

Several of the dancers who attended Catholic schools were expelled for appearing on Bandstand.

A few of the public school kids dropped out of school because schoolmates harassed them.

"I used to try to take back streets so the kids wouldn't notice me," says Eddie Kelly. "I'd get constant razzing. It was really horrific at times."

Bandstand Regulars were beat up outside the studio, knocked onto the el tracks, chased around neighborhoods and called "Bandstand faggots" repeatedly. One regular was jumped at a church dance. Carmen Jimenez sometimes had a police escort to school, and her father picked her up every day.

The horrible treatment helped ground the dancers in reality, and it brought them together as a group. Even now, many of the old gang talk frequently and get together occasionally. Some are practically family - Betty Romantini and Lenny Natale, the only Bandstand Regulars who met on the show and married (and later divorced), made Joe Fusco the godfather to their daughter.

All of the Regulars were unceremoniously cut loose when they turned 18. They lost their ability to walk past the lines to enter the show. Their fan mail disappeared, and their fame diminished. Several of the Regulars tried to capitalize on their popularity by cutting records and hiring agents, but the majority simply receded to their pre-Bandstand days of relative obscurity.

Carrelli still gets recognized.

"You're not THE Justine Carrelli, are you?" fans ask her occasionally.

"I'm 64 now, honey," she responds with a hearty laugh. "I'm not 14 anymore!"

***

"Bandstand really wasn't one of those places that promoted inclusion," says Jannie Blackwell who grew up West Philly and now serves as a city councilperson for the neighborhood. "But the 50's didn't have a lot of race relations."

Blackwell, an African-American, never went to the show but her sister attended several times.

"In spite of all the negatives one could perceive, it was just good, light-hearted fun," the councilwoman says. "People didn't begrudge Bandstand for anything. It was a hit."

It was a hit because Dick Clark was a brilliant social scientist, understanding just how far he could go and still maintain the massive audiences.

Bandstand didn't broadcast twangy, blues-influenced music that emanated from deep within your soul. There were no raw, visceral emotions, and certainly nothing that made you sweat just hearing it - the kind of music Georgie Woods played on his WDAS radio program.

"Rock and roll was rebellion and the thing that Dick Clark feared most was rebellion," says Ray Smith, a Bartram grad who frequented Bandstand and is now crafting a musical revolving around the show. "He made rock and roll palatable to not just a wider audience, but also to a whiter audience."

And Bandstand didn't feature fully integrated crowds like those enjoying the music in Philadelphia. They had a handful of black faces in the crowd occasionally, and that may have been enough to shock people in other parts of the country - and even some Philadelphians.

"It was a model for integrated audiences versus other venues in Philadelphia," says Wilson Goode, the city's first African-American mayor, who spent his teens in West Philly after moving from segregated North Carolina. "For example, the skating rink in my neighborhood only allowed African-Americans to go there one night a week, Tuesday nights. The rest of the time, Elmwood Skating Rink was only white folks."

Bandstand was a gentle transition for Baby Boomers from their parent's isolated generation to the modern world where television forced the country to actually see itself.

***

By 1964, popular culture had changed radically. The doo-wop era gave way to the British Invasion and folk music. The age of innocence was officially over on January 10, 1964 when Bandstand took their production to California.

WFIL owner Walter Annenberg donated the old studio building to WHYY. WFIL moved to City Line Avenue (and later became WPVI which is now 6ABC). WHYY used the building until 1979. The former Bandstand site remained boarded up from 1979 until 1996 when The Enterprise Center renovated the space. They've spent more than $3.7 million to rehab the facility, which is on the National Register of Historic Places.

American Bandstand continued to promote family-friendly pop music, from the Beach Boys to Weird Al Yankovic, on the West Coast until 1989.

***

American Bandstand fulfilled dreams and made stars out of everyday Philadelphians.

"We're restoring that same dream," says The Enterprise Center's Della Clark. "Just now it's not for music and entertainment but for business."

Clark and her staff work with aspiring leaders to navigate government and develop business strategies. The Center has helped hundreds of minority owned companies succeed in construction, accounting and countless other industries.

And the Center takes full advantage of its more famous predecessor.

The old studio is now a conference hall and banquet space with Bandstand memorabilia everywhere. The dais is a copy of Dick Clark's old two-tiered podium. The Center's logo looks like an old 45 record.

"Regardless of its history, whether it was good or bad," Clark says, "it made history."